Below are some quotations from Four-Sided Triangle which are representative of the writing style and content:

In the fraction of a second between the telepaths’ awareness of a hostile something. Out in the black, hollow nothingness of space and the impact of a ferocious, ruinous psychic blow against all living things within the ship, the telepaths had sensed entities something like the dragons of ancient human lore, beasts more clever than beasts, demons more tangible than demons, hungry vortices of aliveness and hate compounded by unknown means out of the thin, tenuous matter between the stars.

What seemed to be dragons to the human mind appeared in the form of gigantic rats in the minds of the partners.

Usually the partners didn’t care much about the human minds with which they were paired for the journey. The partners seemed to take the attitude that human minds were complex and fouled up beyond belief, anyhow. No partner ever questioned the superiority of the human mind, though very few of the partners were much impressed by that superiority.

That’s the trouble with working with cats, thought Underbill. It’s a pity that nothing else anywhere will serve as partner. Cats were all right once you got in touch with them telepathically. They were smart enough to meet the needs of the fight, but their motives and desires were certainly different from those of humans.

It was sort of funny realizing that the partners who were so grim and mature out here in space were the same cute little animals that people had used as pets for thousands of years back on Earth. He had embarrassed himself more than once while on the ground saluting perfectly ordinary non-telepathic cats because he had forgotten for the moment that they were not partners.

He was lucky—he drew the Lady May. The Lady May was the most thoughtful partner he had ever met. In her, the finely bred pedigree mind of a Persian cat had reached one of its highest peaks of development.

His mouth moved heavily as he articulated words. “Don’t call our partners cats. The right thing to call them is partners. They fight for us in a team. You ought to know we call them partners, not cats. How is mine?”

Continuing my investigation of science fiction works by Charles Eric Maine, here is a brief review of The Tide Went Out, which I just finished last night (22/10/2022).

This title was first published in 1959, and tells the story of Philip Wade, a journalist who stumbles on the truth of the consequences of an H-bomb test under the Pacific Ocean. The gigantic atomic explosion unexpectedly blasts a hole through the seabed, allowing the seas of the entire Earth to drain into cavities around its core. No seas, of course, means no rain, and no rain leads to a planet almost devoid of water. For a reason that he cannot fathom and which never becomes completely apparent, Wade is selected to work in the intelligence and propaganda department of the British Government and is tasked with responsibility for disseminating misinformation designed to placate the doomed public. His position should ensure his survival when his team eventually evacuates to the Arctic which, along with the Antarctic, has the only remaining source of fresh water (or any water at all for that matter) on the planet.

The science is admittedly a bit off-beam, but that is not the point of the book. The story is partly a warning against overconfidence in scientific progress (an attitude which was less common in the 1950s than it is today), and partly a character study of a flawed protagonist and how his rationality and gut reactions alter, vacillate, and develop during the unprecedented catastrophe. In a world where morality and ethics have ceased to matter, a man is forced to become inhuman in thought and action. Or is he?

The 2019 British Library Science Fiction Classics edition has an excellent introduction by Mike Ashley which explains the background of this work in comparison to similar novels by other authors of the same era.

Listed below are some noteworthy quotes from the text of the book:“Operation Nutcracker took place on June the seventh. Three hydrogen bombs were exploded in the Kaluiki group of islands in the South Pacific. The first was at an altitude of about five thousand feet. The second—sea level. And the third was the daddy of them all…”

Funny how your standards change in twelve years, Wade thought. As a reporter on a local paper in North London he’d been full of the integrity of true journalism, obsessed with the ideal of objective reporting. But somehow the writers with the gimmicks, who found the unusual angles or sometimes manufactured them, always seemed to get the bylines and the promotion. Imagination seemed to be more important than observation.

The earthquake had been severe and had probably done incalculable damage. His brain was too numbed and fatigued to attempt to add it up. Something was wrong somewhere. This kind of thing just didn’t happen in England.

“Funny thing,” said Wade. “There was no feeling of fear. Just a kind of blank tenseness—like in the war during the air raids. You waited and waited—desensitised.” “The general adaptation syndrome,” Shirley remarked casually…Given a long-term emergency, people stop thinking for a long time. They act instinctively, emotionally. The intellect tends to become paralysed. Their behaviour is dominated by a survival drive.”

The only disquieting note, from Wade’s point of view, was the manner in which the facility for survival was being shared among the human race as a whole. It seemed to him that a ruthless form of selection had been adopted. The inhabitants of the polar evacuation camps were, so far as he could determine, government employees, or the families of government employees, and people of direct importance to the survival drive, such as scientists and technicians and chemists and doctors. The rest of the human race didn’t seem to matter. He supposed that in a situation of this type one had to be ruthless; there had to be the governing class which knew the truth, and the outsiders who were fed with reassuring propaganda to sustain them to the terrible end.

“So you are a lucky man, Mr. Wade. No relatives or friends in important government circles, and yet you are chosen to survive.” A pause, followed by an inscrutable narrowing of the eyes. “Unless, of course, your wife…?” Wade shook his head. “No important relatives whatever.” “Influential friends, perhaps?” “No.” “Oh, well…”

She averted her eyes. “Pornography, I’m afraid—or something pretty near to it. In the papers and on television. You’d be surprised how the circulation of the National Express has grown during the last few days. And last night’s television audience was estimated to be in the thirty million region.” “For what purpose?” Wade asked. “A form of brainwashing—something to distract the mind of the average man from the horrors of everyday life…” “And women?” “Apparently the women don’t matter. The men are the trouble-makers, and the whole propaganda machine is getting to work on the male sex.” “I see,” said Wade. “I suppose a little pornography on the television screen keeps the men off the streets at night…”

But there were subtle changes too on the psychological level. The churches, for instance, were recording a considerable revitalisation of religious worship. In all countries people were entering the House of God in increasing numbers to pray for deliverance.

…the world seemed fantastic and dreamlike. Economics had gone haywire. Money had no value, but nevertheless the privileged ones could get what they wanted without money, could live in the Waldorf, could eat and drink and erect barricades to keep out the unprivileged and violent mob outside. It was a stark division of the world into two classes—the survivors and the non-survivors.

Wade was a changed man in several ways. For one thing he had learned the art of self-control to such an extent that smoking and drinking had ceased to be habitual.

“We are seeing the world destroyed, slowly and inevitably, at the whim of the scientists and politicians.”

“What frightens me, Wade, is that Carey may have been right. I’ve never felt so confused before. Somehow the outside world hasn’t seemed real to us. I never thought of the people out there as human beings—just statistics on paper. I can’t help thinking…” “Why not stop thinking,” Wade suggested, “then you won’t be so confused.”

“Maybe Carey had a conscience,” Wade said. “Maybe he regarded life as something sacred, beyond all policies and politics. And maybe, in the scheme of things, he didn’t consider his own life more important than his principles.”

Your codes of behaviour have to be flexible enough to adapt themselves to changing conditions in the world. You can no more apply the moral code of last year than you could use the standards of, say, a Stone Age man.” Patten wasn’t convinced. “If that’s true, then it applies to Carey as well.” “Yes—except that Carey’s code wasn’t flexible enough. He couldn’t adapt himself, and now he’s dead. Evolution works on that kind of principle.”

“In the meantime I think it will be advisable to destroy all documents and code and cypher records and equipment. Superficially there would appear to be no need, but one can never quite foresee the future, and it is wise to leave no evidence behind.” “Evidence?” “I mean evidence that could be used to show that the government had acted irresponsibly in this crisis.”

In a decaying world there was nothing but decay. But here and now there was still a spark of humanity to illuminate the spiritual darkness.

Brindle was right. Once you’ve been touched by violence you lose something for ever. But for ever is an overstatement. You can only lose something for a lifetime, and you can tolerate a loss for a lifetime.

And the less we’re moved by circumstances, the less power the puppet masters have, and the more tranquil we are in the face of destiny.

Why true love is letting go? Because it’s permitting the world to be free. By letting go we make peace with fate; we’re okay with people having different opinions, the uncertainty of the future, the dreadfulness of the past, and the impermanence of everything.

Isn’t there an advantage to every disadvantage?

Being useless in the eyes of others could be great for one’s health, as it deprives one of the stress and sacrifice of being useful.

If there’s anything that holds us back from being authentic, it's when we design our lives with the purpose of appeasing others.

Not belonging to a group grants us the freedom to look how we want, dress how we want, associate with and love who we want, and think and say what we want, thus, being an ideologically independent thinker who isn’t encumbered by a group’s narrative.

“You have no responsibility to live up to what other people think you ought to accomplish. I have no responsibility to be like they expect me to be. It’s their mistake, not my failing.” Richard Phillips Feynman

The trichotomy of control, however, offers three categories: (1) Things over which we have complete control . (2) Things over which we have no control at all . (3) And things over which we have some but not complete control.

...unnatural as far as the Japanese worldview of wabi-sabi is concerned. Wabi-sabi rejects the pursuit of perfection and embraces the reality of imperfection. The philosophy behind wabi-sabi can help us escape the hamster wheel of chasing an ideal life and teaches us to appreciate existence as it is: perfectly imperfect.

(Henry David Thoreau) As here wrote: “..a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

Being content with little is the ultimate civil disobedience in modern times. It loosens the grip that society has over us, by not needing what they have to offer in exchange for our time and labor. By owning and needing less, our existence becomes less complicated and less stressful.

Epicurus himself chose a simple life, enjoying weak wine, bread, and cheese, and discussing philosophy with friends.

“If thou wilt makes a man happy, add not unto his riches but take away from his desires,” Epicurus once said.

The 19th-century author, geologist, and evolutionary thinker Robert Chambers, for example, stated in a journal that ‘reading’ is an inexpensive way of deriving pleasure…

We should not complain about impermanence, because without impermanence, nothing is possible.

When we cannot change outside circumstances, the only way to move forward is to change ourselves, including how we look at the situation at hand.

The more we want to be free of pain, the more pain we experience.

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Nature has programmed us in such a way that we’re more susceptible to negativity than to positivity.

Trouble arises when we try to control the future. To control the future, the mind tries to think about it as if it were the present.

Even though what’s happened in the past cannot be changed, we’ll always be guessing what happened exactly. First of all, it’s because our experience of past events is limited. We’ve only observed it through our own senses.

Mastery of the world is achieved by letting things take their natural course. You cannot master the world by changing the natural way.

By letting go, we create space for the universe to do its thing. The workings of nature will not cost us any additional energy.

“Comparison is the thief of joy,” American president Theodore Roosevelt once stated.

Marcus Aurelius beautifully described the continual repetition of things and that, in essence, nothing new happens. Everything is familiar and transient. He asked: “Which is why observing life for forty years is as good as a thousand. Would you really see anything new?”

But when we’re finding ourselves in dire straits, and there seems no way out, it’s essential to always remember that everything changes. The worldly winds are unpredictable. One moment they provide us with delight, the other moment with agony.

“This too shall pass”.

But we can choose the position we take towards these circumstances. Pain is certain. Suffering is optional. So, do we give unpleasant circumstances the power to make us miserable, or do we enjoy some honey instead?

Many people either fight or stick their heads in the sand, and never come to terms with how things are. But there’s a way to move forward. And it starts with accepting reality for what it is, which, in some cases, is an act of radicalism.

Radical acceptance means that we acknowledge the stuff that’s excruciatingly painful.

Because what we resist, persists. And what we accept, we move beyond. Some things are up to us, some things aren’t. We can’t change the past.

However, we do control the position we take toward life. As Søren Kierkegaard stated: “Life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forwards.”

Radical acceptance is a powerful act. It means that we take a deep breath, stand up straight, with our shoulders back, and look the abyss straight in the eye. It sends a message to the outside world that we are willing to embrace it, that we don’t cower away from the consequences of doing so, and that we’re confident that we’ll find a way to deal with it.

On the other hand, the mere knowledge that he was different from other people, and different in a way he did not care to reveal, created a barrier that sealed him off from the rest of humanity.

By a process of recording the “brain-waves’—electrical impulses generated by brain cells—on magnetic tape and later playing them back into a psychiatrist’s brain, it is possible to enter the mind of the patient and find out exactly what is wrong with his mind.

The age of instability, of advancing knowledge and increasing ignorance, of soaring standards of living and plunging standards of conduct, of technical refinement and political hooliganism, of spreading education and dwindling culture. The age of opposites in conflict.

“Escape from life—by courtesy of Cinesphere and Paul Zakon. Canned dreams for the multitude, in 3-D Chromacolor, starring Verna Graham herself, of course.” Laura missed the semi-facetious tone of his voice. “Canned dreams,” she echoed thoughtfully.

Zakon said: “Entertainment is not an art, Maxwell. It is a science. It is the science of escape and every production of mine is scientifically planned to provide the maximum amount of escape.”

Zakon released the pressure on his fingers and leaned back in his chair. “There are two lives, Maxwell. Life and unlife. Life is the monotonous routine of dealing with the basic needs of survival for three hundred and sixty-five days each year. Survival, Maxwell. That’s absolute…

That is where unlife comes in. Play can be transitive or intransitive. Active or passive. Half a century ago people relaxed actively. But as time goes on more and more relax passively. They escape to unlife. See what I’m getting at?”

“If you ask me,” Maxwell said candidly, “it’s a publicity angle —and that’s about all.” Stenheimer’s manner became serious. “You’re off the beam, Maxwell. We don’t publicize unlife. We keep quiet about it. You know why? Because it’s dynamite. It’s the most fundamental thing since the discovery of the atom.”

The reality-tone of the escape medium determines the degree of mental absorption of the audience. It is perhaps significant that in the most vivid dreams the reality-tone is such that the sleeper, on waking, may be disappointed to find that the fictional dream situation is not real.

This typifies the difference in emotive context between life and unlife, and as a general rule it can be stated that unlife is invariably more acceptable to the human mind than life.

Since the subjective reality-tone will be indistinguishable from real life, one is impelled to ask: What constitutes reality? Are the human senses arbiters of that distinction, and is the human mind an adequate judge of what is real and what is not?

For in the long run, all we ever know happens deep inside the brain, and reality belongs to the functions of the brain. Once man begins to control and determine those functions, the secret of reality lies within his grasp. Life or unlife, both are absolutes, and both are real.

Any theory involves politics if it involves power. Politics is concerned with the exploitation of power.

“There’s nothing anti-social about unlife, Maxwell. In fact, it acts as a scavenger of society, and removes the more anti-social types from active circulation… And society is the better for their removal. Its economics are better.”

Below are a few quotations from the book:

The pain, for instance—that was a subjective thing. In the physical world of nature there was no such thing as pain;it was a psychoneural reaction characteristic of a sentient being. It could not be measured, weighed or analyzed, but it was real, nonetheless.

"You are alive, but only just,” said the voice tonelessly. "You must obey every instruction. You will remain here under electronic stimulus for five years. During that time you will gain strength and improve. Afterwards, with care and training, you may be able to lave the life of a normal man.”

"Immortality,” Carson whispered. "It’s unbelievable.” "You were dead. Now you are alive,” the doctor pointed out. "We regard death as a curable disease."

"You speak my language very well,” he observed. "Much better than the green-eyed doctor, for instance.” “I was adequately trained. During the five years of your treatment I was assigned to study antique terrestrial English. Our modern language is international and agglutinative. We have syllables derived originally from most of the important languages. All we do is join syllables together to make up more complex ideas. A complete thought—a sentence if you like—is expressed in one word. We think in terms of sentences rather than individual words, just as an architect visualizes the structure rather than the separate bricks.”

Earth has changed considerably since your day. There have been many wars, and for centuries there was universal radioactivity. Earth is a planet of strange mutants, but there are isolated colonies of normal people, like you and me.

The most perfect language is mathematics. A simple formula can express an abstract idea so complex that it could not be communicated in a million words.

There was virtually no emotion among these people; they enjoyed life in a cold-blooded intellectual way, as one might sit down to enjoy a game of chess, and the only apparent motive for seeking pleasure was the gratification that pleasure could provide.

"You must get used to the fact that people come and go,” she advised solemnly. "It is important to avoid affinity and interdependence. We are each of us individual citizens, and in so far as we allow ourselves to become dependent on others, so we fail to give the State the services of a full individual.” " "Is the State more important than the individual?" She smiled reprovingly at him. "The State is the individual, and the individual is the State.

"It all sounds very unsatisfactory to me,” Carson observed sadly. "Why can’t human beings get together to solve their problems instead of attempting to destroy each other?” "They never have done so throughout history.

You, Mr. Carson, may well prove to be the means of saving Earth from itself. As you know, the Martian colony has on three occasions attempted to take over control of Earth in its own interests—but war across millions of miles of space is an extremely difficult and hazardous operation. More than anything, we have needed a symbol, a figurehead to apply a strong psychological thrust to any projected military campaign. It is our belief that you are that symbol.”

First the family, then the tribe, then the political party, and with the abolition of parties the nation, personified in a single leader; and finally the entire planetary population, directed and controlled and governed by an impersonal authority possessing the power to compel obedience.

What is wrong with mankind that his genius should always be channeled into aggression and war?

"If you knew the full history of Earth, Mr. Carson,” she said, "you would realize just how much they need a strong, rational government. It isn’t a question of aggression so much as—how can I put it? Compulsory assistance, perhaps.”

"You seem to have everything well planned,” Carson commented. Mr. Jaff smiled appreciatively. "All action should be the end product of logical, constructive thought. Action without thought is futile, and often destructive.

"Robert Carson,” he (the mutant) said in a toneless rasping voice. "Are you Robert Carson?” Surprisingly the language he was using was not the Martian semantic blend, but rather a slurred adaptation of the older English of Carson’s own era.

Always remember—the brain, once washed, can always be unwashed. It takes time, but it can be done.

Timeliner by Charles Eric Maine

This full-length novel was first published in 1955, and I think it holds up very well considering the age in which it was written.

Essentially, Timeliner is a time travel tale about a scientist working with what is termed "dimensional quadrature". When something goes wrong, Hugh Macklin’s consciousness is flung forward in time, where he inhabits the body of another man. When that man dies, the protagonist’s mind leaps forward again to find another host.

The story was originally written as a radio play called The Einstein Highway and was broadcast by the BBC on 21 February 1954.

Although this story has been heavily criticized by some reviewers, I must admit that I was completely riveted by its narrative. In some ways it reminded me of the 1997 novel Tomorrow and Tomorrow by the British author Charles Sheffield, which I also found highly memorable and poignant.

The character of Hugh Macklin is well developed and introspective. I particularly like the way in which the reader, through the protagonist's eyes, becomes completely convinced of certain truths, whereafter the rug is suddenly pulled out from under the feet of both by a new development or realization. There are several plot twists, a couple of which I did not anticipate. One notable turn of events occurs near the end, and is used as the conclusion, although what will eventually happen to Macklin is left to the imagination of the reader.

Macklin’s visit to the Moon early on in the story is fascinating, since the descriptions of what it would be like to walk on its surface and how objects would appear concur closely with the findings of the first Moon landing some fifteen years later in 1969. The story also avoids the pitfall of being too optimistic about the future. For example, by 2035, men are finding it difficult even to maintain a permanent lunar base.

I am admittedly partial to good time travel yarns, and I love stories which take the reader from the present all the way to the end of time, so Timeliner was right up my street.

I will certainly endeavor to seek out more books by this author, since his writing style seems eminently congenial to my disposition.

Below are a few notable quotations from Timeliner:

Strange how he couldn't even tell a simple lie without feeling vaguely guilty and immoral. That was his trouble—too many damned high-minded principles that made him critical of his every word and deed, as though some inner radar eye were continually monitoring his behavior.

Interplanetary flight was an established fact, but this was still the pioneering phase, and the foothold which mankind had established on Earth's satellite was tenuous and insecure.

The moonbase was already a reality and the first few tough pioneers, living their lives in an environment not hostile to human life, but completely indifferent to it, had already come to regard their everyday task as routine. Magic dies young.

The year was 2035. Lydia had already been in the grave a long, long time. Nobody he had ever known was alive any more. His world had disappeared beneath the remorseless sands of time.

The word "life line" seemed to possess a special significance, for the theory of dimensional quadrature was itself based upon the hypothesis that each individual is an observer moving through a physical body extended in the fourth dimension of time.

"It seems to me," said Macklin after some thought, "that I have settled upon an age even more unstable and warlike than the one in which I lived originally. I always believed that increasing scientific knowledge would bring about a refinement of mankind, a kind of maturing sense of responsibility..." "Then you don't know your mankind," Prenitz retorted.

"Science is the product of intellect. Behavior is the product of emotion and instinct. The two are incompatible and that is why human conduct is inconsistent with scientific attainment. It is the eternal conflict between the god and the animal in man."

"You'd better come with us," said the guard. "They want to talk to you at Headquarters." Macklin shrugged his shoulders and followed them into the jet car. Nazi stuff, he thought. Echoes of the nineteen thirties. Who would have expected to find it in the twenty-fourth century?

For instance, in a universe of science, the scientist must rule. Or again—the first technocrat government was formed to unify the colonists from extinct Earth, and provide a tight and stable organization that could never again permit the abuse of technology in the name of a political creed.

The vidar went blank, leaving Macklin with an increased sense of foreboding. A strange universe with strange technologies separated by what fantastic distances of time and space from the world in which he had been born—yet there was still talk of war and defense and attack. Man had not changed, and probably never would: it was a depressing thought.

"Few men are so just that they can face annihilation for purely altruistic motives," Macklin replied.

His mentality was a product of twentieth-century society, and the progress of more than ten thousand years was completely beyond its scope.

What was the ultimate goal of the perpetual striving of mankind to attain the unattainable, if indeed there was a goal at all? He would never know unless he seized the initiative and moved ahead in time again, defying the precautions of those who had been responsible for sending him to Anthaar.

The human race, from beginning to end, is one continuous life form intersecting a blind physical matrix in four dimensions. All individuals are tied by affinities, those affinities are defined by emotion. After all, emotion is the reactive element linking mind with matter."

"Perhaps. But you will admit that it is the emotions which produce immediately recognizable physical actions. Man's behavior is mainly based on love, fear, hate, pride, and so on. They override the intellect."

The synthetic experiences offered by the machine might conceivably prove to be more attractive than the relatively colorless routine of day-to-day life, and transmitted entertainment might become a dope, a habit-forming narcotic, dissipating the energy and imagination of the race.

"I could try to understand." "You cannot possibly understand. Five million years of evolution and change have passed you by."

THEY set the legs of Cunningham's string-woven bed into pans of water, to keep the scorpions and ants and snakes at bay, and then left him in pitch darkness to his own devices.

It was not considered decent for a boy of twenty-one to do much more than dare to be alive.

I made sure that all those in authority at Peshawur should hate him. That would have been impossible if he had been a fool, or a weak man, or an incompetent; but any good man can be hated easily.

…the British Government, once established in India, was and always has been not to occupy an inch of extra territory until compelled by circumstances. The native states, then, while forbidden to contract alliances with one another or the world outside, and obliged by the letter of written treaties to observe certain fundamental laws imposed on them by the Anglo-Indian Government, were left at liberty to govern themselves. And it was largely the fact that they could and did keep secret what was going on within their borders that enabled the so-called Sepoy Rebellion to get such a smouldering foothold before it burst into a blaze.

No man knows even now how long the fire of rebellion had been burning underground before it showed through the surface; but it is quite obvious that, in spite of the heroism shown by British and loyal native alike when the crash did come, the rebels must have won —and have won easily sheer weight of numbers —had they only used the amazing system solely for the broad, comprehensive purpose for which it was devised. But the sense of power that its ramifications and extent gave birth to also whetted the desires individuals. Each man of any influence at all began to scheme to use the system for the furtherance of his individual ambition. Instead of bending all their energy and craft to the one great object of hurling an unloved conqueror back whence he came, each reigning prince strove to scheme himself head and shoulders above the rest; and each man who wanted to be prince began to plot harder than ever to be one.

There is a blindness, too, quite unexplainable that comes over whole nations sometimes. It is almost like a plague in its mysterious arrival and departure. As before the French Revolution there were almost none of the ruling classes who could read the writing on the wall, so it was in India in the spring of '57. Men saw the signs and could not read their meaning.

It was not at all an easy question, for the love lost between Hindoos and Mohammedans is less than that between dark-skinned men and white —a lot less.

Within —one story up above the courtyard din —in a spacious, richly decorated room that gave on to a gorgeous roof-garden, the Maharajah sat and let himself be fanned by women, who were purchasable for perhaps a tenth of what any of the fans had cost.

Worry, artfully stirred up, is the greatest weapon of them all…

Against all fear; against the weight of what, for lack of worse name, men miscall the Law; Against the Tyranny of Creed; against the hot, Foul Greed of Priest, and Superstition's Maw; Against all man-made Shackles, and a man-made Hell - Alone—At last—Unaided - I REBEL!

Past masters of the art by which superstitious ignorance is swayed, the priests could swing the allegiance of the mob whichever way they chose…

I have tried to be a thorn in your side, and will continue to try to be until this suttee ceases!" "Why," demanded Howrah, "since you are a foreigner with neither influence nor right, do you stay here and behold what you cannot change? Does a snake lie sleeping on an ant-hill? Does a woman watch the butchering of lambs? Yet, do ant-hills cease to be, and are lambs not butchered? Look the other way! Sleep softer in another place!"

Quoth little red jackal, famishing, "Lo, Yonder a priest and a soldier go; You can see farthest, and you ought to know, - Which shall I wander with, carrion crow?" The crow cawed back at him, "Ignorant beast! Soldiers get glory, but none of the feast; Soldiers work hardest, and snaffle the least. Take my advice on it—Follow the priest!"

"Pardon, sahib! I did not know! Am I forgiven?" "Yes," said Cunningham, remembering then that a Rajput, and a Rangar more particularly, thinks about points of etiquette before considering what to eat.

It burst at the moment when India's reins were in the hands of some of the worst incompetents in history.

Rung Ho, bahadur!" "Rung Ho! See you again, Mahommed Gunga!"

This is the second book written by Louise Lawrence, and it was first published in 1972, just one year after her debut novel Andra.

The following are some quotations from this book:

“Coincidence.” “Is it? Coincidence is queer. This is too queer. It’s not only queer, either. It’s something powerful, something dangerous.”

“Sorry I spoke,” Jimmy muttered and swung into the coffee shop. The air was thick with tobacco smoke.

Jane gripped the edge of the table with whitened knuckles and stared at the jukebox behind him. “They don’t need it,” Jane said. They give machines the power to speak and one day they won’t be able to speak or sing. Machines will do it for them. Don’t they know that? Don’t they realize?”

“Some people don’t hear music,” she said. “They only hear noise. And they never see anything, they only watch T.V. They never feel anything deep. They never use their senses at all. They never even think.”

“She’s up there somewhere. She hasn’t had time to get home. She was strung up. She could have done it. Jane could have done it, Alan.” “I don’t believe you,” Alan said quietly.

Alan took a cigarette from the packet on the piano and went to stand beside Nick and stare from the window.

They saw history repeating itself and they retaliated. They reversed their energy process, poured out the starlight they had taken in, destroyed machines.

“She’s my wife,” Nick said. “She’ll do as she’s told.

Below are a number of representative quotes from the book:

Her face was white and sad because the things she had seen did not exist. They were beautiful and only a dream. It made her want to cry.

I will tell Daemon about Syrd's song. I'll write to him. It was good, wasn't it?" "Very good, but the words I found a little difficult to understand." "I know what he means," Andra said softly. "I know exactly what he means. You can chase after something all your life, and when you catch up with it it isn't there. It's gone like a dream. I've seen it.

Lascaux was annoyed with himself. He had expired hundreds of thousands of people. Why should he mind just one more? He knew the answer. He would mind because she was Andra, and he would refuse to do it.

When she could she read fiction, for in fiction she told him there were many facts. And yet he felt disturbed. That child enjoyed reading too much.

"I read it because I want to read it. You heard it. You heard the flow of the words. This isn't just a language, it's beautiful. The things in these books are beautiful, but in this whole horrible subterranean place there is nothing, not one thing, I would class as beautiful. The language we speak is empty and void of any real meaning. Beauty no longer exists."

Her sorrow reached out across the vastness of the room and he felt its intensity. She was very young and her feelings were the violence of youth. He, who was old, had learned to accept

"If you are bitter, Andra, it will not help. The world you read of is gone and no bitterness can make it return."

"There's nothing individual anymore. We work because we have to work not because we want to. And we do the particular work we're assigned to because we can't do any other kind of work even if we want to. We're not people anymore, we're just things. "

"Well, it's difficult to explain. She's a symbol of what we want to be. She's free." "Andra is no more free than we are. She has to do what she's told just as we do." "I know that, but she's free in her mind."

Andra paints pictures she ought not to paint. She teaches you songs you ought not to sing. She rebels against society because she wants to be different. She tells us a way of life that is beyond our conception, but even we in our apathy know it is far pleasanter than life in Sub-city One."

"And the young ones will be wild tonight when they know Andra is not here to read to them. Andra feeds discontent into our minds just by reading Jane Eyre. That book is everything Sub-city One is not. Cromer would go purple in the face if he knew."

Dr. Lascaux is always saying: If you have a hunch, stick to it.

"So what are you afraid of?" her father repeated. "Surely it can't be a person?" said her mother. "You can't be afraid of anyone on Erinos," said Dev. "And if you are," said her father, "there must be something seriously awry with your thinking. Remember what Master Anders says—you should think no evil, for as you think, so shall you be."

Those who controlled the universe—like the Overseers of Erinos—did so for the good of all existence, plant forms, animal forms and people. They could never defy a Galactic Controller, they said.

Thought is the greatest creative power in the universe. As you think, so shall it be.

As Christopher washed the dishes, he began to wonder. If he changed his thoughts, would his feelings change?

It was the same with people, he thought. He ought to accept what they were—Ben-Harran and Kysha and Mahri. Instead, he judged them, good or bad, his mind picking over their faults, condemning instead of accepting, liking or disliking but not respecting.

How can you play the flute with such technical perfection yet not have a clue about music? Don't you ever think about it? Thought is the greatest creative force in the universe, you told me. But you re not creative. You can't even string together a simple sequence of sounds without being taught.

Everything in life was formed of vibrations—molecules and atoms, heat and light, emotion and thought, each had its voice and its song, mostly far beyond the range of human hearing but audible now through the amplifiers nearby.

"So are they evil or stupid?" asked Kysha. "Many may be wise and kind," Mahri said gently. "I don't see any evidence of that!" Kysha retorted. "If I were to separate the strands of sound and focus on the musical vibrations of individuals, you would certainly hear them," Ben-Harran informed her. But they were ineffectual, thought Christopher, like players in an orchestra where most were out of tune and the conductor was insane. What use were a few violins playing perfectly amid the general din?

"People don't want freedom," said Christopher. "Freedom means responsibility," Christopher went on. "And who wants to be responsible for the mess we've made on Earth? No one, Ben-Harran! Given a choice, we vote away our freedom, elect governments to be responsible for us, choose to be ruled. So we may as well be ruled by Atui and the Overseers. At least they care about all people equally, create a just society and ensure the survival of the planet."

"Whatever's wrong with it?" Maelyn exclaimed. "It tried to compute a paradox," said Christopher. Kysha knew how it felt. She could no more choose between Maelyn and Ben-Harran than the Erg Unit could, but for her it was not just an intellectual problem.

"We're none of us perfect," he told her. "Ben-Harran knows that. As he said, we need to know our own darkness, need to know the worst in ourselves in order to overcome it. We learn by our mistakes—

"And kinder, and easier," said Kysha. "It's much easier to be told what to do and how to be than work it out for yourself." "But is it right?" asked Christopher.

Earth would become like Erinos, forever tranquil, forever happy, forever secure. He thought of it longingly, an ideal existence . . . but he did not feel sure it was right.

Kysha stared at him. "But you must have guessed," she said. "Surely no race of beings could be so conceited or so arrogant as to think they're the only intelligent life form in the universe? I mean, there are billions of star systems in thousands of galaxies, so obviously other life forms must exist. It's common sense, isn't it?" But they did, thought Christopher. They did think they were the only intelligent life form in the universe. And if they learned the truth, it would make no difference. A breed unable to accept fellowship even among its own kind would be hardly likely to acknowledge kinship with species such as these.

"It is we who are responsible, Lady of Atui. It is we who make our worlds as they are, each and every one of us."

Had Zeeda been destroyed by a supernova I think you would not be protesting thus. Extinctions happen in the material universe . . . you know that. And what has been lost by this happening? That which is created can never be destroyed, remember? Only its form may be changed . . .

His head denies the wisdom of his heart.

(First Published in 1996)

Below are some representative quotations from the text of Dreamweaver:

She had been taught history at school. The history of Malroth….She had been taught how many people had escaped to Arbroth …. A new world, a new civilization—fairer, simpler—where none were rich and none were poor, and violence was outlawed, and scientific invention strictly vetted and seldom applied. It was how Eth lived, many generations later, in a small unchanging community ruled by the land and the seasons, where people survived by their own labor, helped one another, and shared what they had. But life had not been like that on Malroth, Cable informed her.

"And do you know why?" "No," said Eth. "Because it was ruled entirely by men," said Cable. "That statue you saw was a symbol of their power: El-Tesh, the horned god. He was worshipped there for centuries, an unbalanced religion in which women had no place."

And so, unopposed and with the blessings of El-Tesh, men were free to commit all manner of atrocities. "Which is why we have no orthodox religion on Arbroth," said Cable.

It's why we accept women and men to be of equal importance and why even a child may have a voice. Our only problem is in keeping it that way."

Life sends to each of us the experiences we need in order to grow and develop.

The fierce hatred of the afternoon and all thoughts of revenge had subsided during the castigation Nemony had given her. To assume someone else's emotions as her own, and be willing to act upon them, was nothing short of foolishness, Nemony had said. Feelings were temporary and not to be trusted.

"We all invite what plagues us into our lives," said Mistress Agla. "All that has occurred in Kanderin's life is an opportunity to learn and grow, if she would but see it. And what will she learn from this latest tragedy?

"Ill thoughts damage you," murmured the unseen Eth. "Give rise to bad emotions and unstable behavior. And they were the same, all those frozen people who slept with you, only worse, much worse. "

The ghost from the machine, if we think of our bodies as machines. And are we like her? Do we all have a dream-body within us? If so, what do we feed it on? What do we mean by food for the soul, Dr. Wynn-Stanley?" "….what is it we need other than bread and circuses?"

"What we fear in ourselves we also fear in other people," someone said.

"It's what everyone needs," the old woman murmured. "Somewhere secure, somewhere to be alone in without being lonely, to be ourselves as well as being a part of something bigger. Here is where I belong, I suppose."

"Not just to me. It matters to everyone. It's representative. Representative of everyone who lives on this planet, including you. If we harm those people, if we damage them in any way, then we also damage ourselves and Arbroth. Because our emotions and our actions affect not only our own personal auras, but the aura of our planet as well."

Generations of dream-weavers and acolytes had passed through its halls, but few outside it dreamed of what went on there, or knew the price Eth among others had paid for a green-brown world and a way of life that damaged no one.

Louise Lawrence is probably best known for Children of the Dust, a post-apocalyptic young adult novel which was first published in 1985. Judging by the comments readers have made about that book, it is unforgettably harrowing in its realism. Louise Lawrence also wrote fantasy and science fiction novels, which were generally well received and are remembered fondly by people who were teens in the 1980s and 1990s.

Calling B for Butterfly is the first book by this author that I have read, and I must say that I was suitably impressed by both the writing style and the content.

This is a story about four very different teenagers who are traveling on a colony-bound starship, but who end up having to take care of a baby and a hyperactive toddler when the vessel is ripped apart by an asteroid. Glyn is a disgruntled and inexperienced young steward from Wales who is forced to take charge. Ann is quiet and timid, avoids conflicts, but displays sincerity and inner strength. Matthew is bookish, thoughtful, and gentle, and Sonja is spoiled, impulsive and uncooperative.

All that remains after the disaster is one small area of the main ship and its attached lifeboat. As if that is not enough, after opening the viewing ports on this escape craft, they discover that they are being drawn inexorably toward Jupiter by the planet’s enormous gravitational field.

These four young people, who would under any circumstances experience a clash of personalities, are thrown together in a highly pressurized and seemingly impossible situation. The author handles the characters and the dynamics of their interactions intelligently and realistically, even though Glyn and Sonja may eventually grate on the mind of the reader as they become more and more annoying. It clearly shows that certain personalities are more capable of self-reflection than others, and that people act in various ways under stress and mature at different rates.

Apart from the human element, there is also an alien presence, which may or may not be malevolent. The ending is unexpected and poignant in a subtle and beautiful way. Calling B for Butterfly is definitely not a run-of-the-mill teenage science fiction story, but is unique and quite unforgettable. I have now gone on to read Moonwind by the same author, and right from the very beginning this book also seems to be highly unusual and powerfully imaginative.

This novella by Cordwainer Smith (real name Paul Linebarger) was first published in Galaxy Magazine in October 1962.

The story is set well beyond our time, and is a small part of Smith's enormous future history. The protagonists are Jestocost, a lord of the Instrumentality of Mankind (the rulership during a certain period in this fictional universe when humanity has already expanded into space), and C'mell, a beautiful "underperson" (a descendent of animals genetically engineered to possess human form and intellect, but enjoying no social rights and assigned primarily to performing manual labor). C'mell’s ancestry is derived from cats, so she retains certain abilities and traits peculiar to felines. The name "C'mell" is reportedly derived from that of the author's pet cat, Melanie.

C'mell works as a "girlygirl" (something like an escort) at the main spaceport.

The story centers around the secret ambition of Lord Jestocost to assist the oppressed underpeople in acquiring rights without starting a full-blown revolution or overturning the existing social order.

Through C'mell, Jestocost hopes to contact the presumed leader of the underpeople (a being with incredibly strong telepathic powers), and concoct a scheme by which they can steal information which will allow the underpeople to conceal themselves from The Instrumentality while they work to secure the social rights they desire.

Since the plan requires that Jestocost and C'mell cooperate closely, the story also becomes one of unrequited love which passes into folklore and is passed down to future generations in poetry and songs, hence the cryptic verse which begins the story:

She got the which of the what-she-did,

Hid the bell with a blot, she did,

But she fell in love with a hominid.

Where is the which of the what-she-did?

from THE BALLAD OF LOST

C'MELL

The writing is like nothing I have ever encountered before. The deceptively simple prose possesses a lyric and almost hypnotic quality which leaves incisive imagery and an impression of strong emotion in the mind of the reader. Easily understandable words describe people and situations which are utterly alien in their essence. There is an unforgettable poignancy to the end of the story.

I read "The Ballad of Lost C'Mell" in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Two A, which is part of a collection of the greatest science fiction novellas published before the introduction of the Nebula Awards in 1965, as selected by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America.

In order to understand The Ballad of Lost C'mell more fully, I think I will have to read the novel Norstrilia, which has been described as a sequel to this story, since it apparently includes all of the main characters and is related to the same issues.

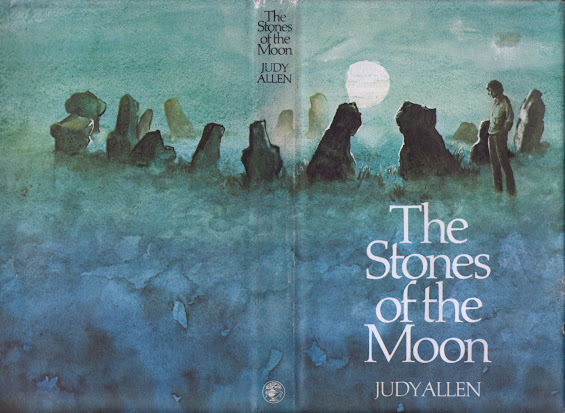

The Spring On The Mountain by Judy Allen

Here are some representative quotations from the book

It was immediately apparent that the first two pictures were portraits of herself. ‘If one thinks, perhaps, that one doesn’t wish to be old,’ she said, ‘it is good to be reminded that one is merely completing something designed a very long time ago.’

No one knows what the cause of the fear was, and it doesn’t really matter. That’s gone long ago. But the emotion itself has become trapped and repeats itself in an endless cycle. The mind usually has to make reasons for such a sensation, and people tend to see whatever they expect or whatever they fear most when it comes upon them.

And why does a cat which has never been to a vet before show fear the moment it is carried inside the door and exposed to the lingering fear of thousands of other animals?’ ‘I just find it very difficult to believe that a chunk of emotion is floating about in the air in the lane,’ said Michael uncomfortably. ‘What sort of things do you find it easy to believe, Michael?’ ‘I believe what my eyes tell me,’ said Michael. ‘Oh dear,’ said Mrs White, throwing up her hands in a parody of horror. ‘You really believe all that illusion? Oh, this is terrible!

Below are a small number of quotations from this book:

…the present is always shaped by the past, even if it isn’t obvious.

‘Must be synchronicity,’ said Ned. ‘Must be what?’ said Kate, who had more or less recovered herself. ‘It has to do with coincidences,’ said Ned. ‘It means if you get a lot of coincidences together there could be an underlying meaning.’

David has limited interest in the mosaic, but becomes fascinated by an ancient stone circle on a nearby hillside. But his interest soon turns to trepidation when he has a strange and inexplicable experience on touching one of the two largest stones.

Although his father dismisses the middle-aged Mr. Westwood, who is staying in the same boarding house, as an eccentric dilettante, David is receptive to the man’s theory that the stones had more than a merely ritual function in ancient times. Westwood thinks that they may have been used to call forth water in times of drought, and he believes that this could be the origin of their name, The Weeping Stones. When Westwood is arrested and held by the police, it is up to David to continue the investigation which the older man started and carry it to its logical conclusion.

After centuries of dormancy, something has reactivated the stones, causing the mill river to rise and threaten to break its banks.

It seems that an unprecedented catastrophe will occur unless David can convince the townspeople of the extraordinary power of the stones, discover the reason behind their reactivation, and turn back the tide of events…

The Stones of the Moon was first published in 1975, and although now available in ebook format, really seems to be a forgotten gem. There are almost no comments about it online. I found it surprisingly sophisticated for a children’s book, and the flaws of the individual characters and the dynamics of their interpersonal relationships added to the realism of the story. In a way it reminded me of the books for young people written by Penelope Lively in that it struck a pleasing balance between an atmosphere of down-to-earth modernity and an air of mysticism.

Below are some quotations from the book which provide an idea of its general tone:

Stone circles were always set up near water, even if the water was only a stream. It may be that nowadays the nearby water-course has long since dried up, but it will have been there when the circle creators were working. In the days before water could be piped to wherever it was needed, all building, all human habitation, all places of work, had to be within reach of water.

‘But how do you have time to learn so much?’ ‘I shall have all the time I need. No man dies before he has finished what he came to do.’ David’s father huffed loudly. ‘I don’t think that’s strictly true,’ he said. ‘Oh, but it is,’ said Mr Westwood, laughing. ‘If I die before I’ve finished, it will mean that this was not my work – I took a wrong turning. But I don’t believe that, I believe I’m on the right lines.’

‘I don’t have a material end in view. But it’s not essential to measure every activity in terms of possible financial reward, you know.’

Within the most fantastic legends there is usually, perhaps always, a kernel of truth.

Then what does astrology tell you?’ said Tim, and for once he actually looked as if he wanted an answer. ‘On a personal level, it can tell you about yourself.’ ‘That’s dull. I know about myself.’ ‘Wonderful. I congratulate you. It’s a rare person who can make such a statement.’

I’m only trying to point out that you can overcome almost anything in your nature – if you understand the problem.

To be at peace one must achieve balance and harmony. This is never easy…

If you wish to look at the world through a coloured filter then do so, but don’t argue with a man who sees the world through his own eyes.

There’s no reasoning with people who want to put a mystical interpretation on everything.

An archaeologist is only somebody who digs things up and catalogues them – that doesn’t mean he’s the only person in the world who can make sense of them.’

A century ago, at the close of the Victorian era, a fortune in gold sovereigns and a unique timepiece were stolen from old Silas Heron. The crime was blamed on a homeless beggar boy, but this was never proven as the items were never recovered and the boy vanished without a trace.

Two watches feature in this story, the Railway Timepiece and the Midwinter Watch. The Railway Timepiece went missing in the days of Silas Heron after his fortune was stolen, and the rightful heir of the old man, Toby Heron, is not even sure whether the Midwinter Watch ever existed. Each watch allows for a subtly different kind of time travel, and if the Midwinter Watch could be found it might enable the user to recover what was apparently stolen a century ago: a king’s ransom in gold coins.

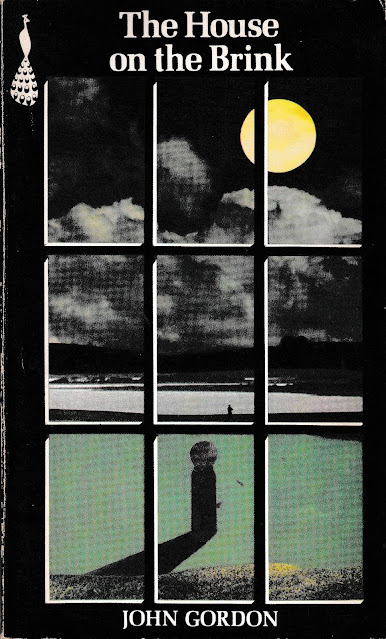

Regarding the personalities of the children and their interactions with each other, there are clear similarities to other works by John Gordon. For example, Sophie could correspond to Jonquil in The Giant Under the Snow, since she is more sensitive to the paranormal and is therefore able to take the lead throughout much of the adventure. Indeed, at first only she can see the apparition of the Starveling Boy which appears at intervals to guide them. Simon is an Arf-like character in that he is highly skeptical and demands scientific proof for everything, often dismissing the experiences of Sophie and Jack as products of overactive imaginations. Jack is the exception, and does not really have a counterpart in The Giant Under the Snow. Jack is intuitive, daring, and quite impulsive. The contrast between young people who believe and others who find reasons not to is a device which appears in most of the novels I have read by this author.

Unlike many of his other books, The Midwinter Watch features fully human villains as the enemy. Tony Heron’s cousin Will and Toby’s former friend Reg Boston are fairly standard rogues who seem to be motivated by nothing more than simple avarice. They intend to use the Railway Timepiece, along with all manner of deceit and coercion, to discover where the Midwinter Watch is hidden. They are cunning and crafty and seem to turn each victory achieved by the children into a defeat. However, as in most tales of this kind, in the end it is the perceptive powers of the children and the action they take which lead to a satisfying conclusion.

I found this book to contain a more straightforward and conventional plot than the other books by John Gordon I have read. The atmosphere and tension are present, but not as intensely as in his other works. And as a collector of children’s timeslip literature, I certainly appreciated the inclusion of time-travel as an integral part of the story.

However, of the books by John Gordon I have read, The Edge of the World still remains my firm favorite. The House on the Brink comes in a close second, and I would place Fen Runners and The Giant Under the Snow together in third place. The Midwinter Watch was entertaining, but I feel I must rank it in fourth place. The Quelling Eye is therefore still my least favorite so far, although it was far from unenjoyable.

How many miles to Babylon?

Three score and ten.

Can I get there by Candlelight?

Yes, and back again.

Beloved Benjamin is Waiting by Jean E. Karl

Following are a few quotes from the book:

Besides, if she had to do it, she could. You could always do what you absolutely had to do. So there was no point in getting upset in advance.

But it was hard to think about. Millions of suns in the Milky Way. And millions of Milky Ways. It made her feel small. And yet it made her feel big, too, because in her mind she could hold such a big idea.

“Get your thoughts away from the situation. Maybe then your mind will show you new things, things your fear now hides from you.”

She quickly laid out all the possibilities; there weren’t many. And then out of the mists in her mind, the answer came: the only thing she could do. It was doing what she had to do, but doing it in a way that would work for her, that would make it possible for her to do it.

“But after the first day, I came because I wanted to—because I liked to talk to you and I liked to see the cemetery. It’s something from another time, isn’t it, Mr. Simon? When people were different and things were easier.”

The House in the Waves by James Hamilton-Paterson

The sea is a recurring theme in this children's book which was written in 1970. Martin, a fourteen-year-old orphan, lives chiefly in his own inner world, which he keeps closed against the outer world so that nothing can hurt him. Since he seems to be gradually drifting away from all meaningful contact with external reality, well-meaning doctors send to him a special home not far from the sea in southeast England (East Anglia). His inner self is dominated by a strange marine world, and he feels inexorably drawn to the coast. One day, when opportunity affords, he runs away to find it. Soon after he sets out he finds a strange balloon with a note tied to it, the writer of which begs anyone who might find it for help. Thus begins the adventure which eventually leads Martin out of his self-imposed emotional isolation. This is an absolutely wonderful story which can be read on many levels, which is what I look for in books written for children and young adults.

The House in the Waves is beautifully written; extraordinary, insightful and totally engrossing. That the plot hinges on a timeslip (whether real or imagined) is also a major bonus.

Below are some quoteworthy passages from the book:

"You have my utmost despision,” she’d yelled after them from the front door, "and I’ll never forgive you — never — never — never—” the last "never” ending in a sob of rage, which was the blackest defeat of all.

From the central drawer she drew out her Book of Strangenesses and turned to the front to her lists of most beautiful and most detested words. Under the beautiful words, which began with "Mediterranean” and "quiver” and "undulating” and "lapis lazuli” and "empyrean,” she added "mellifluous,” which she copied from a piece of paper Mrs. Gray had given her at school.

"Good! I should say you have the stuff of a professional writer in you, quite by instinct, apparently. It’s far better to write an awkward ending than a false one.”

I wonder if I’ll ever have a pain like Mrs. Moore’s. I don’t want to but I’m pretty sure I ought to have all kinds of feelings and pains if I’m going to be a writer.”

But how quickly a day, a mood of happiness, can change. It takes only a few seconds, a word or two, a single, unreflecting gesture.

"Now, that’s a funny thing. Listen, everybody. When you apprehend something, you know it. In other words, you catch on, you have a piece of knowledge. And when you apprehend a villain, you catch him. So you know him better, because you have him.” "That’s right,” said Uncle Phil. "But if you’re apprehensive, it’s because you don’t have knowledge you should have. You’re scared in an anxious way because you don’t know all you should know. It’s the very opposite.

The almost unbelievable fact about Greg was this. On another occasion Uncle Phil had taken them to the Egyptian Museum in San Jose, and Mrs. Redfern, turning from a jewel case, let out a cry when she saw Greg standing under the elbow of the big statue of the Pharaoh Ikhnaton. She went to him and took off his glasses, leaving his face, Julia thought, naked and almost frighteningly unfamiliar. And when you looked back and forth at those two, you would have sworn that Greg and Ikhnaton were twin ' brothers.

"That’s what a poem is,” Leslie said, "a feeling about some special time or place or happening, pressed into as few lines as it will go.”

"Do you mean that that,” exclaimed Paul, "is exactly the way this pharaoh looked?”

"Because when you see the painting, and then Greg, you know everything isn’t just ordinary after all. I mean, there really are mysteries.”

"I see what you’re thinking. It seems Mrs. Moore and I believe that nobody’s to blame for anything, because who knows what the parents did. But there’s no point in being alive, it seems to me, if a person never changes. Somehow he has to see himself from the outside —”

"If you have to, you will. If there’s something you must do, you do it — it’s as if it’s handed to you.”

by Susan Cooper

...the hedges that were the marks of ancient fields - very ancient, as Will had always known; more ancient than anything in his world except the hills themselves, and the trees.

For all times co-exist, and the future can sometimes affect the past, even though the past is a road that leads to the future... But men cannot understand this.

'He will have a sweet picture of the Dark to attract him, as men so often do, and beside it he will set all the demands of the Light, which are heavy and always will be. All the while he will be nursing his resentment of the way I might have had him give up his life without reward. You can be sure the Dark makes no sign of demanding any such thing - yet. Indeed, its lords never risk demanding death, but only offer a black life...'

'There's not really any before and after, is there?' he said. 'Everything that matters is outside Time.'

'They are English,' Merriman said. 'Quite right,' said Will's father. 'Splendid in adversity, tedious when safe. Never content, in fact.'

Decades ago, a boy called Tom Townsend was skating with friends along a Fenland canal named Dutchman's Cut when he fell through the ice under Cottle's Bridge. Afterwards he felt sure that something pulled him down into the dark waters. Switching to the present, a boy swimming in the very same spot finds a piece of metal and a small shell-like scale under the mud on the bed of the channel. Taking it home, Kit (Christopher) discovers that the metal is one of Tom's lost ice-skates. From the time he brings the ice-skate to the surface, he becomes aware of the same shadowy figures that Tom’s granddaughter Jenny has been seeing for some time, and together they gradually learn that an ancient evil is stirring out in the fens. Of course, it is Kit and Jenny who are tasked with the responsibility to take the action needed to make things right again.

Fen Runners is not as long, intense or thorough as The Edge of the World. However, its charm lies in its succinctness and appropriate turn of phrase. Although it is a relatively quiet book, there is nevertheless excitement, a slight element of horror, shadows in the darkness, and a vividly-realized winter setting. It takes an author of great skill to draw a reader completely into another world in relatively few pages, and John Gordon manages this superbly in Fen Runners.

Fen Runners is a short read with a compelling and memorable atmosphere, solid characters, and a timeless sense of adventure. Indeed, an impression of timelessness permeates the whole book, especially when the lonely areas of fenland are described. I think I enjoyed this book as much as I did The Giant Under the Snow, but the plot was perhaps not as convincing as that which unfolds in The Edge of the World.

Well, now that I have read the three works by John Gordon which I have as etexts, the challenge is to acquire his other fantasy books!

The Edge of the World is a YA fantasy novel first published in 1983. It primarily tells the story of Tekker and his friend Kit, who discover that through moving small objects with their minds (telekinesis) they are able to open up a parallel dimension in the English Fenlands. However, the parallel world is far from being a marsh, but is a burning-hot barren red desert from which ‘horseheads’ emerge. These nightmarish creatures have empty horses skulls, but walk upright on two legs.

Although they are warned not to open the parallel dimension by an old man who once went there and lost what was dearest to him, Kit and Tekker are forced to do so when the controller of the horseheads, a reclusive local woman, harms the mind of Kit’s brother, Dan, and he slips into a coma-like state and then nearer and nearer to death. The only way to undo the damage is to restore a key artifact to the possession of someone who is imprisoned beyond the desert.

The Edge of the World has all the characteristics of the most gripping adventure stories, and the world-building is sublime. The reader can really become immersed in the story and feel the experiences through the eyes of the protagonists, who are fully fleshed-out complex characters. The paradoxical antagonism and attraction between Tekker and Kit is handled particularly well.

I noticed similarities between this book and the more well-known The Giant Under the Snow. Apart from the tense atmosphere, the sneeringly skeptical character of Dan reminded me of Arf from the latter book. At one point, Arf tries to convince himself that nothing is stalking him in the forest by rationalizing the movement he sees as the nearer trees sliding over a background of those further away as he walks forward. In The Edge of the World, the same device is used with the boulders in the desert.

"She was sure the heads had moved. 'Wait!' She held his arm. The rounded shapes, many as tall as themselves, lay still. She had been tricked by the way they overlapped."

John Gordon's writing is highly incisive and the plot is fast-paced, immersive and exciting. The interaction between the characters is realistic, and the juxtaposition of the real world and the parallel dimension adds to the surreal nature of the imagery. Most books of this ilk end with the parallel world eventually being closed off forever from those who had visited it, but Gordon adroitly avoids this cliche in his finale.

The only details which date the book to the era in which it was written are Tekker's occasional slightly disparaging comments about girls, and the part where they decide to try hitchhiking to get back to their home village. Hitchhiking children and teens seem to appear quite often in novels from the 1960s and 1970s.

I must say that I enjoyed this book more than The Giant Under the Snow, and that I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys good fantasy literature and is not too disturbed by a touch of horror.

Below is a sampling of quotations from the story which highlight the high quality of the writing and story content:

"'I think just about anything's possible, Kit. You've only got to learn the knack.'"

"'My trade. French polisher. Spent most of my life putting a shine on things and that’s a kind of deception. It can fool you. Look at the top of this table and you don’t see a table. There’s the window, see?' He pointed at its reflection. 'And the ceiling. And then deeper down a kind of darkness, like a pool. Deep. Dark. Anything could be there.'

"'There's always something just beyond the edge of things, and sometimes you learn the trick of getting there.'"

"A wall of sheer glass rose straight upwards – a sheet so pure it was like clear water falling from the roof of the sky, but hanging motionless like time stopped, burning with a burst of sun at its base but glistening so high overhead it could have been stars. It had a knife-edge. It seemed too tall to stand. It seemed to sing with the sheer effort of standing in the sky."

The Giant Under the Snow

By John Gordon

By Susan Cooper

Of course, while the basic outline of the story was feasible when this book was published in the early 1970s, it could hardly happen today, for children suddenly disappearing would result in frantic parents, police and social services fearing the worst and taking immediate action to find them. And it is unlikely that a good-natured elderly man travelling alone would dare give two children a lift along the way for fear of what he might be accused of later. For this reason, the 1970s environment The Driftway describes is as much a piece of history as the other more distant happenings that the road reveals to Paul.

The book is relatively short at around 150 pages, but the author has a talent for conveying the power of events and feelings using a minimum of words. And in common with her other novel, Astercote, Penelope Lively describes physical locations as possessing characteristics and powers resulting from the events which occurred in them in the past. It is probably right to say that the author’s love for her homeland and the stories it holds is at the heart of The Driftway. The strong sense of a past peopled with individuals who were perhaps not so different from us makes a trip down the Driftway a worthwhile endeavor.

Below are some noteworthy quotes from the book:

…if the place is a special place - and at the right time other people can pick up that shadow. Like a message, see? Messages about being happy, or frightened or downright miserable. Messages that cut through time like it wasn’t there, because they’re about things that are the same for everybody, and always have been, and always will be. That’s what the Driftway is: a place where people have left messages for one another.’

‘Places go on. They last a sight longer than people do. And the names of places. They’re old, always. From old times. From the people that made them first, cleared the land and that.’

It’s the same stream, Paul thought, the same stream the boy talked about. He heard it like I can hear it now, and saw that long flat hill just the same as I see it.

‘You know something else, son? The first time you get yourself worked up about other people - strangers, people you’ve never known, never will know - that’s when you’re beginning to grow up. You’re learning. Mind, some people never do, and they’re the ones you want to look out for. There’s a lot of harm can come from them.’

There you are, you see. Things don’t happen in circles. It’s more like dropping a stone into a pond: you make ripples and they bump into each other and make more ripples.

You see the way the shape of a country’s made the people in it, and you see the way they’ve written themselves all over it, too, people who’re dead and gone now. In the way the fields go, and the roads, and the things they’ve built, and the bits they’ve dug up or cut down or flooded or drained or not been able to find a use for at all.’

Most people look at a bit of country and they just see it as an arrangement of hedges, and trees, and lanes, and they don’t think of how it’s all come about, like. They think it’s natural. There’s hardly such a thing as a natural landscape. It’s something that’s always on the move, changing every few years. And if you get to know a bit about it you can see all the layers of changes, going right back into old times: where there’s been a village that’s gone now, or a road that’s got forgotten, like this one…

The fog rolled back before the cart, revealing a tree, a twist in the track, a clump of cow-parsley heads splayed against the hedge: he imagined other eyes in other times looking at the same things, feeling the same feelings, thinking ... No, not thinking the same things. That would be the difference.

‘You can’t know how they thought,’ he said. ‘Not really.’

‘I s’pose not, son. But we should try. We should do that.’

Soon as you’re ready to believe another bloke might not be exactly what you think he is, you’re halfway to being able to live with him. Or work with him, or whatever it is.’

You think everything’s happening just to you, he thought, but it isn’t. It’s happening to other people too. It sounds obvious when you say it, but it isn’t till you think about it.

Adam by A.K. Stone

Astercote by Penelope Lively

Time at the Top by Edward Ormondroyd

The Root Cellar by Janet Lunn

Rose is miserable in her new home, partly due to the fact that she has no experience of communicating with other young people, and partly because the family's way of life seems so disorganized compared to that of her very prim grandmother.

Shortly after her arrival, Rose accidentally discovers an abandoned root cellar, and quickly realizes that if she steps inside at just the right moment, she will emerge in the middle of the nineteenth century. She meets a girl named Susan who works for the parents of a boy named Will Morrissay. Susan, Will and Rose enjoy a wonderful day together, and Rose feels she has found a place where she really belongs.

Rose returns briefly to her own time for three days, and then on returning to the past is shocked to discover that Susan has aged three years. Will has gone off to fight in the Civil War. By that time, the war has been over for some months, but Will has not returned, and Susan has not heard anything from or about him.

After doing some historical research in her own time, Rose returns to the past, and with Susan embarks on a trip to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to learn what has happened to Will. Since many people in Susan’s time naturally think Rose is a boy because of her short hair, she decides to dress like a boy to provide a little added protection on the trip.

The historical accuracy regarding the nineteenth-century environment and US Civil War is impressive. War in general is portrayed in a very realistic way, and an antiwar and anti-nationalist message is conveyed persuasively through the comments of disillusioned soldiers and the descriptions of their circumstances.

The journey changes Rose from being a self-absorbed girl who looked down on her country-bumpkin relatives into a brave and empathetic young woman. In this way, the book is as much about what it means to be an individual as it is about time travel or history. To quote the book itself:

She remembered that she had thought about marrying Will. She thought about Susan, who wanted only one thing, to have Will home, and about her own self not really knowing what she wanted or even who she was. “Being a person’s too hard,” she thought. “It’s just too hard.”

Indeed, a major theme running throughout this story is the difficulty of not knowing where you belong or even who you are as an individual, and not being able to comprehend all of the factors at play in the world, factors that might occasionally serve to your benefit, but which just as often could bring you harm.

As with other successful works about time travel, for example Tom’s Midnight Garden, much of the poignancy is saved until the end, where all the threads of the story are drawn together and the full significance for the protagonist becomes clear.

Eventually, through experiences both joyful and heartbreaking, Rose comes to understand what is most important, and to know what she wants and where she belongs. All this makes for an emotionally satisfying conclusion.