Hellflower by George O. Smith

This 1953 novel is a decent enough space adventure with some good ideas which are central to the story. Modern readers will likely find the dialog and mode of expression rather dated. Since the story takes place in the future, I am a little surprised that the author did not try harder to use a less contemporary manner of speech, but the fact is that many of the conversations feel as though they belong in a 1940s spy or gangster movie.

Nevertheless, the story about a wronged and exiled spaceship captain (Farradyne) being recruited by a law enforcement agency in order to bring the leaders of a notorious narcotics ring to justice and thereby win back his place in society was sufficiently interesting to keep me reading until the end. The nature of the narcotic involved (the hellflower) is pretty original (although, strangely, it only works on women), and the truth about the power which lies behind the criminals ensures that everyone gets much more than they bargain for.

Hellflower is primarily an action adventure with little depth of introspection or characterization, and is pretty typical of the pulp fiction of the era. As such, in my opinion, it cannot compare with Smith’s 1959 novel The Fourth “R” (AKA The Brain Machine) in quality, as the latter work exhibits a more mature writing style, and is much more thought-provoking and philosophical.

Here are some representative quotations from the book:

“Funny how a guy gets out of his kid-habits,” mused Cahill. “And even funnier how he wants to go and do it all over again but never quite makes it the same.”

“Cahill was always a damned fool,” nodded Niles. “He was a dame-crazy idiot and it served him right. Some men prefer money, power or model railroads. Women are poison.”

Farradyne burned with resentment at any proposition whereby he, who had not committed anything more than a few misdemeanors and some rather normal fun and games which are listed on the books but are likely to be overlooked, should be less cultured, less successful and less poised than this family of low-grade vultures. If anything, the attitude of Mrs. Niles shocked him more than the acts of her husband.

In the background was the muted sibilant of the reaction motor, a sound like the shush of a distant seashore. Farradyne heard these sounds unconsciously. They were as pleasant to the ears of the spaceman as the sounds of a sailing ship were to the oldtime seaman.

The Lancaster made one more complex turn as the end of the punched tape entered the autopilot.

Coldly and calmly Farradyne scanned the skies. Providing they had not travelled more than forty or fifty light years, the constellations before and behind the direct line of flight should be reasonably undistorted,

Man’s inhumanity to man was a pale and insignificant affair compared to the animal ferocity of a woman about to settle up a long-standing account with another woman.

The warp generator permits a top speed of about two light years per hour in Terran figures.

Excitement would carry a person through a lot of trials.

The law of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth is only good when there is a higher authority to see that it goes no further.

The Fourth “R” (AKA The Brain Machine) by George O. Smith

I stumbled onto this 1959 novel by George Smith quite by accident, and I am glad that I did. The story is about a five-year-old boy whose parents have invented an electromechanical educator which can imprint knowledge indelibly on the brain without the student having to go through the normal more arduous channels. Very soon, with his parents out of the picture and his very life in danger, young James Holden finds that he must fend for himself. But how can a five-year-old boy hide out and make his way in a society geared principally toward the needs and ambitions of adults?

At the same time, James desires to rebuild his parents’ machine at a secret location, and use it to complete his own education. However, in order to achieve this, he will undoubtedly need reliable and loyal helpers and a facade to hide behind until he comes of age or can prove that he has the competence to take on the responsibilities of an adult.

This was a thoroughly enjoyable book which was well written and thought provoking. Although it is set in America, I felt that it had an almost English quality to it, perhaps because it reminded me somewhat of the Hampdenshire Wonder by J.D. Beresford. The tension is skilfully maintained throughout, and along with the introspective ruminations of the protagonist and the bildungsroman aspect, is one of the factors that makes it a compelling read.

According to the Internet reviews I have glanced at, The Fourth “R” appears to be a favorite among the novels of George O. Smith, and somewhat atypical in that it is not a space-opera adventure like many of his other works.

By the way, the Fourth “R” is evidently what the machine cannot teach. The “Rs” logically must refer to the four “Rs” of education, but since there are various versions of these, readers have come to different conclusions regarding what the Fourth “R” actually stands for. The book itself does not explicitly provide an answer.

Here are some quotations taken directly from the text of the novel:

It is deplorable that adults are not as friendly and helpful to one another as they are to children; it might make for a more pleasant world.

They cohabited but did not live together for almost a year; Paul Brennan finally pointed out that Organized Society might permit a couple of geniuses to become research hermits, but Organized Society still took a dim view of cohabitation without a license.

….two years prior to the date that Louis Holden first identified the fine-line wave-shapes that went with determined ideas. When he recorded them and played them back, his brain re-traced its original line of thought, and he could not even make a mental revision of the way his thoughts were arranged.

Knowledge is stored by rote.

He was trapped in the world of grown-ups that believed a lying adult before they would even consider the truth of a child.

But no one is more difficult to fool than a child—even a normal child.

He had yet to learn about the vast gulf that lies between theory and practice.

children denied their contemporaries for playmates often take on attitudes beyond their years.

It has something to do with the same effect one gets out of studying. On Tuesday one can read a page of textbook and not grasp a word of it. Successive readings help only a little. Then in about a week it all becomes quite clear, just as if the brain had sorted it and filed it logically among the other bits of information.

James Holden evaluated all people in his own terms, he believed that everybody was just as eager for knowledge as he was. So he was surprised to find that Mrs. Bagley’s desire for extended education only included such information as would make her own immediate personal problems easier. Mrs. Bagley was the first one of the mass of people James was destined to meet who not only did not know how or why things worked, but further had no intention whatsoever of finding out.

James Holden’s mechanical educator was a wonderful machine, but there were some aspects of knowledge that it was not equipped to impart. The glandular comprehension of love was one such; there were others. In all of his hours under the machine James had not learned how personalities change and grow. And yet there was a textbook case right before his eyes.

Tim Fisher said, “Me—? Now, I need a drink!” James chuckled, “Alcoholic, of course—which is Pi to seven decimal places if you ever need it. Just count the letters.”

All the wealth of his education could not diminish that odd sense of the time-factor that convinces all people that the length of the years diminish as age increases.

It was fun while it lasted, but it didn’t last very long. It awakened him to the realization that knowledge is not the end-all of life, and that a full understanding of the words, the medical terms, and the biology involved did not tell him a thing about this primary drive of all life.

But it took a shock of such violence to make James realize that clams, guppies, worms, fleas, cats, dogs, and the great whales reproduced their kind; intellect, education and mature competence under law had nothing to do with the process whatsoever.

“As Mark Twain once said, ‘When I was seventeen, I was ashamed at the ignorance of my father, but by the time I was twenty-one I was amazed to discover how much the old man had learned in four short years!’

Tau Zero by Poul Anderson

Over the years, I have mostly enjoyed the books by Poul Anderson which I have read. I loved the Time Patrol Series, There Will Be Time, The Man Who Came Early, and The Boat of a Million Years. So Tau Zero, which is highly regarded by many readers, has been on my reading list for quite some time.

Tau Zero differs from the above works in that it includes many more elements of ‘hard’ science fiction, or you could say the author utilizes known scientific principles in realistic ways to advance the plot. According to the reviews that I have perused on the Internet, some readers have therefore felt that the story is rather dry and the scientific descriptions not easy to comprehend. I did not have this problem myself, and I think that anyone who has read a fair amount of science fiction literature and is also interested in science would not encounter this kind of difficulty. The reader only needs to have a basic grasp of Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity to make the story perfectly understandable.

Strong Points:

- Anderson’s writing is sometimes pulpy and at times lyrical, but it is always highly readable.

- Some fairly complex scientific ideas are integrated seamlessly and convincingly into the narrative.

- The epic nature of this novel which takes us all the way to the end of time and beyond makes it a compelling read.

Weaker Points:

- The characterization is satisfactory but not wonderful. The female characters seem to be slightly more fleshed out than most of the male characters, certain of whom seem to be almost interchangeable with each other.

- The interpersonal dynamics of the characters is also rather unrealistic and melodramatic, especially in the frequent rearrangements of the romantic liaisons. I think I expected more mature and stable behavior from a crew which had supposedly been picked from among the very best that mankind had to offer. Since the promiscuity does have a negative psychological effect on crew members, I would have thought that this was something to be avoided by professionals, at least during the voyage itself (a case is made later on in the book for why it might be beneficial once a planetary colony has been established). I put the preoccupation with sexual relationships down to the fact that the book was written at the end of the 1960s and published in 1970, so it apparently reflects the spirit of free love which emerged in that era.

- The principal character, Reymont, is brusque and abrasive in his manner (probably necessarily so with such an undisciplined crew to keep in order), but he never seems to be wrong about anything at all throughout the story.

In conclusion, I think that, despite its flaws, there are good reasons why Tau Zero Is regarded as a science fiction classic, and why many people are still reading it today.

Below are some quotations from the book itself:

At age twenty-five, an Academy graduate with a notable performance in the interplanetary ships, he was allowed on the first crew for Epsilon Eridani. They returned twenty-nine years later; but because of the time dilation, they had experienced just eleven, including the six spent at the goal planets.

“I want to lie awhile alone anyway and think.”“About Earth?”“About many things. We are leaving more than most of us have yet understood, Charles Reymont. It is a kind of death— followed by resurrection, perhaps, but nonetheless a death.”

Consider: a single light-year is an inconceivable abyss. Denumerable but inconceivable. At an ordinary speed— say, a reasonable pace for a car in megalopolitan traffic, two kilometers per minute— you would consume almost nine million years in crossing it. And in Sol’s neighborhood, the stars averaged some nine light-years apart. Beta Virginis was thirty-two distant.

Precisely because there is an absolute limiting speed (at which light travels in vacuo; likewise neutrinos) there is an interdependence of space, time, matter, and energy. The tau factor enters the equations.

True, the closed ecology, the reclamations, are not 100 per cent efficient. They will suffer slow losses, slow degrading. A spaceship is not a world. Man is not quite the clever designer and large-scale builder that God is.” His smile was ghastly.

Her folk continued regardless to follow Earth’s calendar, including observances for the tiny congregations of different religions. Each seventh morning, Captain Telander led his handful of Protestants in divine service.

Total sensory deprivation quickly causes the human mind to lose its hold on reality. Deprived of the data-flow with which it is meant to deal, the brain spews forth hallucinations, goes irrational, and finally collapses into lunacy. The effects of prolonged sensory impoverishment are slower, subtler, but in many ways more destructive.

The human animal wants a father-mother image but, at the same time, resents being disciplined. You can get stability like this: The ultimate authority-source is kept remote, godlike, practically unapproachable. Your immediate superior is a mean son of a bitch who makes you toe the mark and whom you therefore detest. But his own superior is as kind and sympathetic as rank allows.

They talked business for half an hour. (Centuries passed beyond the hull.)

Journalists delighted in trumpeting that another Earthlike world had been discovered. The fact always was, however, that this was one possible interpretation of our data. Only one among numerous possible size and orbit distributions. And subject to a gross probable error.

What is man, that he should outlive his God?”

“So make your peace. Interior peace. That’s the only kind which ever existed anyway. The exterior fight goes on. I propose we wage it with no thought of surrender.”

“We can’t deny what’s about to happen is awesome. But so is everything else. Always. I never thought stars were more mysterious, or had more magic, than flowers.”

Infinity Beach by Jack McDevitt

Infinity Beach, first published in 2000, is set on a colony planet called Greenway, which has three moons, and a single continent in a worldwide ocean. The planet was originally barren before terraforming took place, but it has now been seeded with life from Earth. It is one of the “Nine Worlds” linked by regular interstellar flights. The society of Greenway is peaceful and prosperous, and people may choose between a pursuing a profession or living in relatively comfortable idleness supported by government subsidies.

The humans of the Nine Worlds have concluded that they are probably alone in the universe and that no other spacefaring civilizations exist. The urge to explore has therefore all but died out along with the accompanying curiosity, resulting in increasing cultural stagnation. And this is worrying to some, who fear they may be witnessing the start of a new dark age.

Politicians are content with the status quo, and are resistant to change, and the only ones swimming against the tide of apathy are scientists who have devised a project to artificially detonate a series of novas at precise intervals in order to send a last signal out into the universe and hope that any aliens will take note and seek out humanity in a few millennia.

Years previously, a small group of idealists had steered their spaceship, the Hunter, out into the unexplored depths of the Belt of Orion seeking a first-contact experience. However, due to experiencing engine problems, they were soon forced return to Greenway without ever reaching their destination. Soon after arrival at the space port, female crew members Emily and Yoshi vanished without a trace, and of the remaining two male members, one died in a mysterious explosion, and the other fell into a depression and retired into obscurity. Thereafter, the region around the explosion was rumored to be haunted, and the population moved away.

Now, a couple of decades later, Emily’s sister, Kim Brandywine, who has never really given up the hope of finding out what happened to her sibling, has her curiosity piqued by her former teacher and (at first reluctantly) agrees to investigate the affair, even though most others would prefer to leave it buried.

This is a murder mystery with plenty of descriptions of sleuthing, which is really what this author seems to do best. It is also an imaginative first-contact novel which develops in a unique way, and is (in my opinion) somewhat stronger than most of the Alex Benedict novels. I often find that McDevitt's standalone stories are better than the ones which belong to a series.

Jack McDevitt may be described as a good storyteller first and foremost, and a science fiction writer second. Infinity Beach probably would not be classed as "hard" science fiction, but it definitely possesses elements of that genre. It may thus appeal to quite a wide range of readers, as there are big ideas without technical complexity.

The characterizations are fairly good, but the strong point is the pacing, which quickens as Kim becomes more and more convinced that something is amiss and that only she can bring the truth to light. And, of course, at the end of the twisting, turning plot, she finally manages to achieve just that.

Following are some pertinent quotations from the text of the book:

“It’s obvious that Whoever designed the cosmos wanted to put distance between His creatures.”

We’re trying to say hello in a scientific way, but nobody expects a reply for millennia.

But the extension of life had underscored quite clearly what scientists had always known: that truly creative work must be done during the early years, or it will not be done at all. Genius fades quickly, like the rose in midsummer.

The surface of Lake Remorse gleamed in the sun. The skeletal houses provided a grotesque mixture of transience and majesty. Kim wondered what it was about desolation that inevitably seemed so compelling.

Kim had sworn she’d never do anything like it herself. When someone is gone, she’d decided, she’s gone . Using technology to pretend otherwise is sick . It had turned out to be easier to make the pledge than to keep it, though.

The belief that society was in decline was a permanent characteristic of every era. People always believed they lived in a crumbling world. They themselves were of course okay, but everybody around them was headed downhill.

No two interstellar liners look completely alike. Even those sharing the same basic design are painted and outfitted so there can be no question of their uniqueness. Some have a kind of rococo appearance, like a vast manor house brought in from the last century; others resemble malls, complete with walkways and parks; and still others have the brisk efficiency of a modern hotel complex. Starships, of course, have few limitations with regard to design, the prime specification being simply that they not disintegrate during acceleration or course change.

There must be a part of us, she thought, that’s wired to accept the paranormal. Science and the experience of a lifetime don’t count for much when the lights go out.

“The problem with that,” she said, “is that we’ve become complacent and self satisfied. Bored. We’re shutting down everything that made us worthwhile as a species.” “Kim, I think you’re overstating things.” “Maybe. But I think we need something to light a fire under us. The universe has become boring. We go to ten thousand star systems and they’re always the same. Always quiet. Always sterile.”

One assumes the kindness of a friend; But the kindness of a stranger, Ah, that is of a different order of magnitude— —SHEYEL TOLLIVER, Notebooks, 573

“Cyclic development,” Kim explained. Dark ages. Up and down. “It looks as if we can’t rely on automatic progress. We’ve had a couple of dark ages ourselves. The big one, after Rome, and a smaller one, here. The road doesn’t always move forward.”

But the species may have learned something. Survey’s exploration teams, who are carrying on the search for whoever else might be out there, are extensively trained in how to respond to a contact. Similar training is now required of anyone seeking to purchase or pilot a deep-space vessel.

Polaris by Jack McDevitt

This is the second of nine books about the far-future antiquities dealer Alex Benedict and his assistant Chase Kolpath. Like the first book, A Talent for War, it is a mystery the unraveling of which requires advanced problem-solving skills and unrelenting persistence on the part of the two protagonists.

Sixty years previously the space yacht Polaris failed to return from a scientific research expedition, even though the captain had sent a message saying that she and her passengers would be getting underway imminently. The ship was found, but no trace ever materialized of any of those on board. Alex manages to purchase certain artifacts from the Polaris for his clients, but someone begins to show more than a casual amount of interest in what he has procured, spelling danger for both himself and his pilot Chase.

Polaris has many points in common with A Talent for War, but the narrator this time is Chase Kolpath and not Alex Benedict. Alex seemed a lot more diffident and self-effacing when he narrated his own story in the first book, but Chase describes him as much more confident and capable, with a degree of nonchalance. The author also tells us that more than a decade has passed since the events of A Talent for War, so that may also partly account for the differences in Alex’s personality.

Strong Points:

Flowing narrative style which is easy to read.

Fascinating Mary-Celeste-style mystery which unravels at a gradual but appropriate pace.

Interesting technologies and convincing historical background.

Weaker Points:

Somewhat bland characterizations.

Society feels too much like 21st Century America (except for a crime rate so low that it has rendered the police somewhat incompetent for lack of practice at solving cases, and the continued use of paper notepads) for it to be a realistic depiction of how humans might live ten millennia from now.

In summary, Polaris is a mystery story in a science fiction setting. The strength of this work, and probably the whole series of nine books, lies in the logical processes and attention to detail involved in the detective work which eventually reveals the truth. Readers who enjoy mystery novels and space operas will likely enjoy it, whereas those who prefer more speculative fiction at least partially based on current scientific knowledge might not find it so satisfying.

Here are some quotations from Polaris:

It was odd, living through an event twice. But that was what FTL did for you. When you could outrun light, you could travel in time.

Alex has commented that being dead for a sufficiently long time guarantees your reputation. It won’t matter that you never did anything while you were alive; but if you can arrange things so your name shows up, say, on a broken wall in a desert, or on a slab recounting delivery of a shipment of camels, you are guaranteed instant celebrity. Scholars will talk about you in hushed tones.

History used to be simpler back when there wasn’t so much of it.

History is a collection of a few facts and a substantial assortment of rumors, lies, exaggerations, and self-defense. As time passes, it becomes increasingly difficult to separate the various categories. —Anna Greenstein,The Urge to Empire

Antiquities are . . . remnants of history which have casually escaped the shipwreck of time.—Francis BaconThe Advancement of Learning

All things, even virtue, are best in moderation.

I began to suspect we were seeing patterns where none existed. There were all kinds of studies that showed people tended to find the things they looked for, even if some imagination was required.

“That’s the way for most of us,” Alex said. “Birth, death, and good riddance. The world takes no note. Unless you’re lucky enough to overturn somebody’s favorite mythology.”

“Hogwash. Chase, you’re babbling. All that is fine when you’re talking in the abstract. Death is acceptable as part of the human condition as long as we mean somebody else. As long as we are only talking statistics and other people. Preferably strangers.”

Youth is an illusion, Chase. We are none of us young. We are born old. If a century seems like a long time to someone like you, let me assure you that the annual round of seasons and holidays becomes a blur as the years pass.”

The problem the police have is that there are almost no crimes. So when one happens, they’re more or less at a loss.

But in a broader context, we can argue that all the workings of the cosmos seem designed to produce a conscious entity. To produce something that can detach itself from the rest of the universe, stand back, and appreciate the vault of stars. Birds and reptiles are not impressed by majesty. If we were not here, the great sweep of the heavens would be of no consequence.

Alex wrote something in a paper notebook.

We imagine that we have some control over events. But in fact we are all adrift in currents and eddies that sweep us about, carrying some downstream to sunlit banks, and others onto the rocks.—Tulisofala, Mountain Passes (Translated by Leisha Tanner)

The power of illusion derives primarily from the fact that people are inclined to see what they expect to see. If an event is open to more than a single interpretation, be assured the audience will draw its conclusion ready-made from its collective pocket. This is the simple truth at the heart of stage magic. And also of politics, religion, and ordinary human intercourse.—The Great Mannheim

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore, So do our minutes hasten to their end.—William Shakespeare

Time Wants a Skeleton by Ross Rocklynne

Ross Rocklynne was a science fiction writer who primarily published short stories and novellas in Astounding and Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine between the 1930s and 1960s, although most of his work was published in the thirties and forties.

I read Time Wants a Skeleton (1941) mainly because my interest was piqued by the title. Tony Crow is a law enforcer who chases three criminals to where they land on a large rock in the Asteroid Belt of our Solar System. Unfortunately, his ship crashes, but he is still determined to make his arrests. A short while after leaving his craft, he comes upon a human skeleton a in narrow cave, which he just “knows” existed before the advent of the human race. Just how such a situation could be possible is the central mystery running through this novella.

The writing itself is dated, and the plot development somewhat convoluted. The premise is fascinating, but the execution rather clumsy. Of course, there is certain behavior and dialogue which is likely to make the modern reader cringe slightly. I found it possible to suspend belief and accept the (pseudo)scientific explanations (as far as they go), but these sometimes feel as though they fail to mesh seamlessly with the story.

The asteroid on which Tony lands is described as "a twenty-mile planetoid more than a hundred million miles removed from Earth." And yet, strangely enough, Tony and the outlaws are able to move around and fire guns at each other as though the gravity was the same as that on their home planet. This oversight on the part of the author is especially egregious considering that gravity plays a key role in the rest of the tale.

This novella is mildly entertaining, but like many modern readers, I think I only carried on until the end to discover the true origin of the skeleton. Having said that, the story does appear in various anthologies of representative science fiction works from the period, and some of the “scientific” explanations are creative and imaginative.

Here are some quotations from the story:

"Oh," he said carelessly, "a theory goes the rounds the asteroids used to be a planet. They're not sure the theory is right, so they send a few bearded long faces out to trace down faults and strata and striations on one asteroid and link them up with others. The girl's old man was just about to nail down 1007 and 70 and Ceres. Good for him."

She said: "Gravitons are the ultimate particle of matter. There are 1846 (sic) in a proton, one in an electron, which is the reason why a proton is 1846 (sic) times as heavy as an electron…..When we want to move the ship, the gravitons are released. They spread through the ship and everything in the ship. "The natural place for a graviton is in a proton. The gravitons rush for the protons—which are already saturated with 1846 gravitons. Gravitons are unable to remain free in three-dimensional space. They escape along the time line, into the past. The reaction contracts the atoms of the ship and everything in the ship, and shoves it forward along the opposite space-time line—forward into the future and forward in space. In the apparent space of a second, therefore, the ship can travel thousands of miles, with no acceleration effects.

"I'm old now, son—you know? And I've seen a lot. I don't disbelieve anything.

She winced. "I'll….. stay in my room except when I cook…..You can keep everybody out of the ship." (My comment: there are a number of men on board, but apparently only the woman does the cooking! Well, it was 1941.)

"I do not know whether we are shaping a future that is, or whether a future that is is shaping us.

He was the last man on a lost world. And even though he was doomed to death in this unimaginably furious crack-up, he should have some goal, something to live for up to the very moment of death!

Future and present demanded cooperation, if there was to be a logical future!

The mere fact of time-travel presupposes duplicity of existence. Our ship and everything in it was made of electrons that existed somewhere else at the same time—a hundred million years ago, on the pre-asteroid world. You can't get away from it.

A Talent for War by Jack McDevitt

I must confess that I have a penchant for science fiction stories about space archeology. For example, I enjoyed Henry Beam Piper’s Omnilingual, and the Heritage Universe Series by Charles Sheffield, as well as Jack McDevitt’s The Engines of God and Deepsix.

A Talent for War (first published in 1989) is the first title in a series of books (now numbering nine) starring Alex Benedict, a dealer in antiques and archeological relics, who lives around 10, 000 years in the future when "a thousand billion human beings" are scattered across the "several hundred worlds" that form a loose confederacy of planets within our galaxy.

The title may lead some to imagine that this is a work of military science fiction, but it would be more appropriate to class it as a mystery or detective novel with a futuristic setting, although military strategy is discussed at many points throughout the book.

Alex was raised by his uncle Gabe, a xenoarcheologist, but the two have become estranged due to the uncle’s disapproval of his nephew’s profession. When Gabriel Benedict disappears and is presumed dead, Alex receives an enigmatic last message from him describing an incredibly important historical discovery. However, the find is related to such a sensitive issue that no details are vouchsafed in the communication.

A Talent for War is the story of Alex’s pursuit of his uncle’s discovery.

For me, this book ticks all the right boxes. There is history, archeology, future technology, a realistic alien culture, excellent world building, and a tantalizing mystery which is uncovered very gradually, and even then not in its entirety. In some ways, probably due to the amount of detective work involved, it reminded me somewhat of Inherit the Stars by James P. Hogan.

Alex and his pilot and assistant Chase Kolpath uncover evidence that the well-known historical account of the pivotal event which occurred during a war two centuries previously may be very different from the truth, and that forces on both sides of the conflict do not wish the accepted narrative to be corrected. The sophisticated backstory is revealed slowly and carefully, but gathers pace as the past becomes perilously relevant to the present and future.

Some of the A.I. and other devices described are pretty visionary considering that the book was written in the 1980s, but at the same time there are many references to “buttons” and “switches”, which even now in our age are being superseded by newer technologies. Paper books are still common Alex’s time, which struck me as a little odd, although of course it is possible that books in their traditional form will endure, as they do possess certain qualities unmatched by electronic formats.

McDevitt certainly makes us care about both the protagonists of the story and the historical characters whom Alex is researching, and it is made abundantly clear that the history is of great importance to the world Alex lives in.

The author refrains from providing definite answers to every question. The reader is therefore encouraged to become think and actively participate, piecing together clues and reaching conclusions that the narrative itself may not explicitly reveal. This is an element which adds realism to the world which the McDevitt creates. Another aspect which has a similar effect are the quotations from various famous people of the future which form short introductions to each chapter and which reflect a broad range of beliefs of convictions.

Alex is initially reluctant to undertake the task of finding out the truth, but every time he thinks about backing out, he meets with disapproval from Chase. Nevertheless, by the end of the book it is Chase who is having serious misgivings about their whole enterprise in the face of what seems like Alex's increasingly reckless behavior. So there is an interesting role reversal, since Alex discovers after all his historical research into military strategy, that he himself may possess something of a talent for war.

A Talent for War may disappoint readers who enjoy faster pacing and plenty of action, but for me the slow and thoughtful pace along with the multilayered complexity was suitably satisfying. And in the two places where action does occur, it is engaging and exciting.

Following are a few quotations from the narrative of the book:

In those days, you never knew when you’d arrive at a destination. Vessels traveling through Armstrong space could not determine their position with regard to the outside world. That made navigation a trifle uncertain.

Gabe had done what he could to hold onto the wilderness area. It had been a losing fight, as struggles against progress always are.

Again and again, she put the question to her journal, and eventually, I suppose, to us: How does one account for the fact that a race can espouse the ideals of a Tulisofala, can compose great music, and create exquisite rock gardens, and still behave like barbarians?

Original ambitions and objectives get lost, each side comes to believe its own propaganda, economies become dependent on the hostile environment, and political careers are built around the common danger. Consequently the cycle of war-making tightens and will not stop until one side or the other is exhausted.

Eventually, I went back and reread the “Leisha.”

Lost pilot,

She rides her solitary orbit

Far from Rigel,

Seeking by night

The starry wheel.

Adrift in ancient seas,

It marks the long year round,

Nine on the rim,

Two at the hub.

And she,

Wandering,

Knows neither port,

Nor rest,

Nor me.

Warfare among the aliens has traditionally been carried out on a formal, ritualistic basis. Opposing forces are expected to announce their intentions well in advance, draw up on opposite sides of the battle zone, exchange salutes, and, at an agreed-upon moment, commence hostilities. Sim, of course, fights in the classical human mode. Which is to say that he cannot be trusted.

….wisdom consists in recognizing what is truly important. And in treating with suspicion any cherished belief whose truth is so clear that one need not put it to the test. Among our people, we maintain that wisdom consists in recognizing the extent to which one is prone to error.”

I was still thinking about it, wondering how events could have gone so wrong when everyone seemed to want to do the right thing. Weren’t perceptions worth anything at all? I have no answers, other than a suspicion that there is something relentlessly seductive about conflict. And that, after all these millennia, we still don’t understand the nature of the beast.

I sat that morning, watching crowds that had never known organized bloodshed, and wondered whether Kindrel Lee wasn’t right when she argued that the real risk to us all comes not from this or that group of outsiders, but from our own desperate need to create Alexanders, and to follow them enthusiastically onto whatever parapets they may choose to blunder.

Man is fed with fables through life, and leaves it in the belief he knows something of what has been passing, when in truth he has known nothing but what has passed under his own eye. —Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Thomas Cooper

There is this about comedy: even when it’s bad, it provides a sense of a secure existence, in which things are under control.

Boundaries have no existence save on charts or in small minds. Nature does not draw lines.

Treasures of Morrow by Helen Mary Hoover

This book is a worthy sequel to Children of Morrow published three years previously in 1973. Like the first book, it achieves a good balance between introspection and action. The first part handles the adjustment of the children, Tia and Rabbit, to a society very different from that in which they had lived during their formative years. The second half is the account of the Morrowan expedition back to the place from which they rescued the two youngsters.

The true purpose of revisiting the repressive society which had abused the children is not made absolutely clear, and I think that the author may have done this deliberately. It is ostensibly an anthropological mission to allow the Morrowans to understand more about the only other surviving human settlement they had ever been able to locate. However, if that were the only reason, they could have made such observations the first time they visited, and there would be no need to take Tia and Rabbit along, something which Tia in particular greatly fears. Moreover, they do not seem to engage in much anthropological research when they have the opportunity, and they occasionally commit the kinds of errors which might populate an anthropologist’s nightmares, although this may because the local people make matters difficult for them.

Of course, if you had for generations believed that your community was the only one which had survived a global disaster and continued to develop, it could be exciting to find another, and forming ties with that other society might seem desirable. Although the Morrowans possess many virtues, older readers may discern that they are not without their flaws, one of which is a belief in their own superiority. In conclusion, the return to the original home of the children may have served several purposes, one of them being to make absolutely certain that Tia and Rabbit belonged with the Morrowans, to contribute to their training, and to confirm that no other potential people of Morrow were living in that community.

On the whole, I think that this story is as profound or as flawed as the reader wants to make it. Much more could have been said about how the children adjust to Morrowan society, ideals, and ways of thinking, but I liked the fact that it does not have the ideal ending that many young readers may expect, as this adds to its realism and originality.

Here are some of the more interesting quotations from the story:

But available records covering the decade known as The Death of the Seas indicated that over 93 percent of all living creatures on the earth’s surface and under the seas died by simple suffocation.

Solar radiation through the thin atmosphere had made fertility the exception instead of the rule, the “normal” abnormal. Fathers were privileged men of rank.

This is the story of what happened to Tia and Rabbit when they left a primitive, repressive society and entered overnight into a culture centuries more advanced.

Almost ever since she could remember, Morrow had been a dream, beautiful, unobtainable. Now it was soon to become reality and if reality spoiled that dream, then she had nothing.

And she perceived a new fact, that the sound of one’s voice created its own image for the listener, one which might differ from both the physical aspect and the mind of the speaker, and enhance or distract from the transmission of ideas.

Mature Morrowans seldom used the slow imprecise verbal method of communication among themselves.

If you recall the unchallenged power of your Major, total authority destroys all privacy. It leads ultimately to madness.

A good mind, even when unbalanced, does not destroy to retain power. It seduces.

Her life and her position in life had changed so radically in the past month that she found it hard to accept. Logic told her she was no longer a pariah. Conditioning was not so quickly changed.

Tia and Rabbit were chronologically children, but so different from the Morrowan—so crudely cynical and suspicious of others.

For all their intelligence, she thought, there were a lot of things Morrowans didn’t know. They had never been hungry or cold. They had never had to live being scared all the time. Even when they were little, nobody ever beat them. And when you had to live that way, you had to learn how to put up with it. What right did any Morrowan have to feel sorry for her and Rabbit? The two of them had been smart enough to live through it. She doubted if any Morrowan her age or Rabbit’s could do that.

It was all part of their education, this work. He showed them how he cut and taped a graft so that new life flowed into it from the parent shoot. “We are grafts, Rabbit and I,” thought Tia. “I wonder if we will ‘take’?”

How do you establish trust in a mind that has known too much betrayal?”

As speech lost its great importance, gradually and without any conscious effort, Rabbit’s stutter disappeared. As if, now that he no longer had to talk, he felt free to do so.

You’re too clean and quiet. They won’t even think you’re strong enough to be dangerous. But they might worship the cars.” “That is primitive,” Elaine sneered. “No,” answered Tia. “That is ignorance.”

If you destroy their faith, when you have nothing to give them in its place, you act without ethics. You take all and give nothing.

We look better, cleaner, and well fed and dressed. But none of them asked why.

But now it was enough to know that she had an innate sense of ethics that enabled her to put aside desire for personal revenge and see the picture whole.

Children of Morrow by Helen Mary Hoover

Helen Mary Hoover wrote two post-apocalyptic stories about an organization/settlement named Morrow.

Children of Morrow (1973)

Treasures of Morrow (1976)

At present, I have only read Children of Morrow, so I am assuming that the Treasures of Morrow (which I will read next) is a sequel which will continue the story. In general, the earlier work seems to receive better reviews that the later one.

Again, I am impressed by this author’s skills in several areas:

- A flowing and highly readable writing style

- Excellent world building and the creation of highly immersive environments

- Convincing and likable principal characters whom it is easy to care about

- A satisfyingly deep level of introspection on the part of the young protagonist

- A tight plot which moves along apace (the entire story is told in only around 150 pages)

It is relatively rare to find all of these points covered so expertly in a single young adult science fiction book. The first book I read by Hoover was This Time of Darkness, and I enjoyed it immensely. Children of Morrow is at least as good, and takes me back thirty years to my teens in the UK (the 1980s) when I was reading juvenile literature of similar quality.

Children of Morrow is related in at least one way to the two young adult science fiction books by the English-Canadian writer Monica Hughes I have just recently finished reading (Devil on my Back and The Dream Catcher), since telepathy plays a key role in the story. While the books by Hughes are satisfying, I have found Hoover’s works to be more mature and sophisticated, particularly in the use of language and the descriptions innermost feelings and technologies.

Below is list of more the difficult vocabulary in the book:

blazon

torula

talus

sessile

gamely

vomitus

As you can see, Hoover did not avoid using uncommon words, so apart from the imagination-broadening story content, teens reading her books also have the opportunity to expand their vocabulary.

In my opinion, Children of Morrow is a fantastic example of classic young adult science fiction from the 1980s, and it can be enjoyed by teens and adults alike. I hope that Treasures of Morrow is of a similar caliber

Following are some good quotations from the narrative of the story:

His appearance and speech made him the butt of the Family’s jokes, most of them cruel. Their laughter had made his stammer worse with each passing year.

She saw heads swivel as the women watched him pass and then quickly turned their attention again to the dais where the Major stood. But they were not fast enough. The Major glared at them in anger. “I see the attention of the women is wandering. Of course that is to be expected with women. They have always lacked discipline.” He paused for dramatic effect while the men laughed obediently at his sarcasm.

“Only the Ancient Fathers of the Base who worshipped the Great Missile were left alive! In His mercy He allowed our Ancient Fathers to take in and save women who would have surely died otherwise. Only by their discipline and obedience to their Major and to God were those people kept alive. And it is still only by discipline and obedience to me that you shall continue to live!

To Tia, the Missile was only another sacred relic, none of which she venerated. She had no more fear of it than she had of the rocks in the hills. But she was afraid of the Major and the Fathers. Because of that fear, she kept her beliefs to herself.

Tia knew her mother was ashamed of her but she still blushed there in the dark at the bottom of the stairs. It was bad enough that she was so tall and ugly. That could be forgiven; many strange-looking children were born. Fortunately most of them died in infancy. But when she was three or four, she couldn’t remember now, the knowing had started, and after that, the Dreams. These would not be forgiven by the Fathers.

And, unfortunately, in the old race of man, the individuals most likely to survive great catastrophe were seldom the most sensitive, or even the most intelligent. Merely the strongest in arms and stomach.

In the decade preceding the period known as The Death of the Seas, Morrow, with the foresight, knowledge, and idealism typical of his approach to both business and life, along with his profound love for and belief in mankind, conceived and caused to be created this structure, LIFESPAN, the ultimate in protective human environments.

There was great panic as mankind finally realized the end was near. There was widespread rioting, starvation, disease. Suicide and murder took enormous tolls. But available records covering the decade known as The Death of the Seas indicated over 93 per cent of all living creatures on the earth’s surface and under the seas died by simple suffocation.

Ashira still could not understand why, knowing they were destroying their own world, the old societies could not have stopped it.

“Loving is never unwise—so long as you see the object of your love as an individual and not as a distorted reflection of your own mind.

Since dinner was to be followed by a Council meeting, no wine was served. It had long ago been shown that alcohol produced an adverse effect on both logic and communication.

The thought would not bear holding and she broke off and stared at an ant hill near her feet, the ants busily going about their jobs of carrying sand grains. If she moved her foot she could squash them all, destroy their home. But she didn’t.

There is a cultic element to the society in which the protagonist Tia lives. There is a passage which states:

“Why haven’t the hunters seen these animals?” she suddenly asked Rabbit. “M-maybe they have?” “Then why don’t they ever catch them?” “M-maybe they’re too big—m-maybe they’re afraid of them?” “Maybe.” But Tia didn’t believe it. The Fathers had lied. For some reason they wanted the people to work very hard. Why?

The leaders of the community want the people to work very hard in order to keep them under control by allowing them no time to rest or to think. Religious cults in the real world frequently use this tactic in order to control their followers.

“It’s strange,” Ashira entered into his mood, “the old civilizations dreamed of finding extraterrestrial creatures. Yet they paid so little heed to the life forms on their own planet.”

But Tia shut them out. So far as she was concerned, she and Rabbit were alone. She still believed the ship might come. But in her life and experience, good things that “might be” had seldom, if ever, happened.

The Dream Catcher by Monica Hughes

This sequel to Devil on My Back (1984) was published in 1986. The story meshes well with the first book by describing the experiences of people living in another one of the domed cities, this time Ark Three. A fifteen-year-old girl named Ruth is having trouble fitting into the harmonious and egalitarian society, and begins to have dreams which seem to originate from a source on the other side of the mountains outside the Ark. Old records from during the era of chaos and confusion when the domed were built indicate that Ark One is located in that region, so the people of Ark Three select an expeditionary team to venture outside their protective dome in order to make contact with its inhabitants. They are totally unprepared for what awaits them at Ark One.

On the whole, there is seamless continuity between Devil on My Back and The Dream Catcher, although there was one detail which was different and which I cannot account for:

“The muscled man was Treefeller, and she guessed from the conversation that he was Arbor's father, and that Swift and Healhand were the parents of Rowan and a mischievous boy called Groundsel.”

In Devil on My Back, Arbor is Rowan's younger brother, and Groundsel is the son of Treefeller. At first I just concluded that Ruth must have guessed wrongly, but the relationships are described several times by the author in the second book as they appear above. Did the author have a specific reason for making these changes, or did she simply inadvertently mix up the details? I really do not know.

Many readers prefer the first book, and consider the second weak by comparison, but I did not find that to be the case. The books show how two communities given the same start in almost identical environments could develop very differently depending on the individuals involved. The first book is more action-oriented, whereas the second contains more introspective content, which I appreciated. My only slight grumble with both books is that the interpersonal dynamics and ways in which people react to situations are a little too predictable and cliched. Other than that, The Dream Catcher is another pretty solid and enjoyable work of juvenile dystopian science fiction from the 1980s.

Below are some representative quotations from the book:

There weren't many places where a person could be alone. Being together in a group was what Ark Three was all about, what the Web was about. And she had to be alone. That was one of the things that made her so different.

Nobody had ever left the Ark, not since it had been built at the beginning of the Age of Confusion that followed the last of the oil, a hundred and forty years before. That was the purpose of the Ark, to protect the people and their knowledge from the madness that lay outside.

THERE was nothing to stop a person leaving the Ark, any more than there is anything to stop a person jumping off a ship into a raging sea. It was understood: no one in her right mind would leave the warm togetherness of the Web for the cold empty loneliness of Outside.

What was there beyond the eastern mountains that drew her as iron filings are drawn to a magnet? That was where her dream had come from, and somewhere beyond that range of hills was something without which she would never be whole.

The Protector had carried out his threat and put her in the Black Hole. The ultimate punishment on Ark Three.

Above all there was a hunger for beauty. After a time Ruth began to associate this feeling with the red- haired girl, the girl with the dimple. The girl with the hoe.

….a society that does nothing more than hold onto what it believes is bound for self-destruction. To survive one must grow. To grow one must reach out. To reach out one must risk.

“In the beginning of the Age of Confusion that followed the End of Oil, the Arks were built by different faculties of the University in an attempt to protect the knowledge and wisdom of humankind, which was in danger, as in times before, of being totally lost. “We in the Humanities were charged with guarding and developing our skills in communication and understanding

It was decided that each Ark should be entirely independent, with no communication between them. So, if one failed or was overcome by the forces of the rabble, the others might still survive intact.

“I mentioned two dreams, Warden. In the second kind I get no clear pictures. They are distorted and scary, and I seem to be inside this person - Tomi.”

Ruth found it hard to cope with the prickliness that was growing inside her. She needed so badly to reach out to this unknown person - no, these two people - the one in whom she dreamed, Tomi, and the other, the girl with red hair.

WHAT WERE the people of Ark One really like? They seemed to be a mass of contradictions, living in a domed city, and yet in wooden houses in the forest, culturing yeast proteins and yet killing for food.

He looked around the familiar room. Here in this place was the accumulated know- ledge of the world. In one small room. But then the genius of Michelangelo, or of Einstein or Madame Curie were contained in braincases far far smaller. Perhaps after all the computer was not so great a miracle as the mind of the person who first thought of it.

Devil on My Back by Monica Hughes

I have a penchant for juvenile science fiction from the 1970s and 1980s, probably because it reminds me of my youth and the wonderful stories I read at that time by authors like John Christopher. I also revert to young adult literature from yesteryear when I am dealing with health problems and find it hard to concentrate on more mature works of science fiction. This is the first book by Monica Hughes that I have read, and my feelings about it changed as the novel progressed.

Devil on My Back was first published in 1984, and on the surface seems pretty typical of novels aimed at teenagers in that it includes adventure along with a coming-of-age story and dilemmas involving authority figures and the yearning to find a place where one really belongs.

Fourteen-year-old Tomi lives a privileged life in a domed city which was built to protect some of the survivors of a global breakdown of civilization. Life changes suddenly and drastically for Tomi when events beyond his control result in his ending up outside the protective environment where he grew up. How can he survive alone in the wilderness beyond the dome, and what will he learn by attempting to do so? Is there any chance of returning to his parents and the status he enjoyed before, and would such an outcome be desirable anyway?

First of all, I must say that although many similar ideas have appeared in books before and since Monica Hughes wrote Devil on My Back, this story is quite original in its content. I am sure that I would have thoroughly enjoyed it and found it highly memorable had I read it in my early teens. Some thirty-five years later, as a more seasoned and experienced reader of science fiction, I was reasonably certain that the plot would prove to be fairly predictable, and in some ways it did. Nevertheless, I was completely wrong in the ending I envisaged. The author cleverly employed a twist in the tale which renders the whole story much more meaningful and balanced than it would have been if she had settled for a more conventional ending. The finale also binds the narrative together more tightly, and makes sense of certain seemingly inconsequential details which were mentioned early on in the book. What originally seemed to be a blanket indictment of technology thereby takes on a much more reasonable aspect.

I had some trouble fitting this book to a particular age group. At first, I thought that it was likely aimed at readers in their early teens, but as the content and language developed (and a couple of examples of mild swearing appeared), I altered my opinion to include older teens. Thus, this work is probably suitable for young people aged anywhere between twelve and eighteen years. The sensitively-handled and understated love interest between Tomi and another character adds poignancy to the story and seems to confirm this conclusion.

Since Devil on My Back was well-written and enjoyable, I will now continue directly on to its sequel, The Dream Catcher, which is set in the same world.

Here are some quotations from the text of the story:

Seventy-Three suddenly looked up, straight into Tomi's eyes. It gave him a shock, looking straight into the eyes of a slave. They were as human as his and quite young. He wondered who Seventy-Three had been before the implant failure had led to a slave's life.

You have acquired some knowledge over these years: a week with a mathpak, a week with ancient history, a week with science. Now we have reached the most important day in your young lives: Access Day.

"Why do we access this way if it is so easy to fail?" He blurted out. "Is it only luck that separates us Lords from soldiers or workers or even slaves? I don't understand anything."

You ask if it is all luck? Perhaps it is. All life is luck if you look at it one way. It is luck that your ancestors were part of the ArcOne team during the Disaster. It is luck that your forefathers lived safely underground through the Age of Confusion. It is luck that you were born as sons of Lords. It is all luck. Now ask yourself: is that a useful thing to know?"

Even Seventy-Three congratulated him. But of course there was an honor in being the slave of one of the chief families: an honor to the House was also an honor to its slaves. Tomi nodded casually and went on thinking about the Togethering and the Feast. He never noticed the hurt expression on the slave’s face.

"We are all free, Rowan, remember. You are free to stay with us, Tomi, to share our shelter and food and learn to gather food yourself, to repair and clean...""That is not Lord's work." Tomi drew himself up. "Or you are free to leave." Swift went on as if Tomi hadn't spoken. "Free to move north or south, east or west. Free to be warm if you can make a fire, or to be cold if you cannot. Free to eat if you have the skill to snare an animal or go hungry if you cannot. Free to pick berries and dig roots, eat them and live—or die. Out here in the forest you are quite free."

Each person had something to add to the store of food: a basket of roots or berries, a string slung with fish, a couple of birds, a rabbit. Each returning person was welcomed by the others with a hug or a kiss. Savages, thought Tomi, unnoticed in the shadows. Why, his parents, the Lord and Lady Bentt, would never even touch each other in public, much less kiss. And nobody had ever hugged him that he could remember. He suddenly remembered the morning of Accession Day, when he had been so nervous and Seventy-Three had reached out and gently squeezed his foot. Had that really been the most loving moment of his life: the touch of a slave? He pushed the thought out of his mind. Just savages, he told himself firmly.

Another voice from across the circle took up the story. "The Arab States collapsed with the last of the oil in 2005 A.D. Then followed the Age of Confusion."

"Each small part of the nation had to make its own rules and its own plan for survival. One such plan was ArcOne. ArcOne was a magnificent dream."

She even taught him the proper way to climb a tree and how to stop the earth from spinning around when he looked down. "You are the center of wherever you are," she told him. "And you are doing. You are not being done to. You have to tell yourself that."

Then Rowan came running down the hill to meet him. "Here, give me one basket," she panted. "We share the loads, remember? "I wish you could share mine, thought Tomi. No, I don't. I take that back. You're so good. I wouldn't want you even to guess how horrible I really am inside.

"The son of the Lord-High-Muck-a-Muck was called Tomi. Him they killed in the slave rebellion last September. I saw him once. Fat stuck-up little bastard." He chuckled. "He was no loss!"

"You didn't have my advantages, you see." "Huh?" "Well, it stands to reason. I was next to free already, wasn't I? I didn't have nothing but my shovel and I threw that away. You had your family and your nice home and your robes and your paks and your head filled with knowledge. But you got free in spite of all that, didn't you?"

It was very difficult to be wise, Tomi was learning. It was so much easier to be generous.

He thought about Man and Woman battling the Ice Age, sustained by the great mammals that were their food. Then, as the ice receded, came the freedom to move and to gather food as you moved. Agriculture. The City. The whole history of societies built up and destroyed, knowledge building upon knowledge, knowledge shared and knowledge hidden, knowledge forgotten, subverted, misunderstood. So often nearly lost for ever.

In the Dark Ages, when life became in many parts of Europe a simple struggle for existence against disease, ignorance and the Viking hordes, it was the monks, on tiny headlands, and islands scattered through the seas around Ireland, Scotland and the north of England, who had kept the lamp of knowledge burning, so that Renaissance Man might build upon it.

The Defiant Agents by Andre Norton

In this 1962 novel, Travis Fox, Apache descendant and star of Galactic Derelict, this time pits his wits and physical agility against the Reds (revised in the 2000 edition of The Time Traders to the Russians), the Starmen, and others when he is transported to the distant world of Topaz unconscious and without his explicit consent as part Operation Cochise, a Western move to colonize a planet ahead of the Russians.

Travis and the two animal companions who enjoy a telepathic link with him soon unexpectedly stumble upon another group of settlers who have escaped from the Russian camp and are trying to evade recapture. Travis must strive to overcome the prejudices of his Apache compatriots and those other colonists in an effort to unite them against a common enemy. At the same time, since the planet Topaz was one of those marked on the tapes recovered from the home planet of the ancient Starmen (see the novel Galactic Derelict), Travis also experiences an increasing measure of uneasiness and a feeling that danger worse than anything he can imagine is lying dormant and waiting to strike...

In common with The Time Traders and Galactic Derelict, The Defiant Agents is primarily an action adventure about survival against the odds in harsh environments. There are problems to solve and enemies to eliminate, and there is a central mystery which adds tension and foreboding to the atmosphere. Although it must be said that this novel is somewhat lacking in introspective depth and any greatly profound meaning, it is nevertheless an absorbing and fast-paced story with strong characters and some suitably interesting concepts.

Below are some representative quotations from the text of the book:One was the goal toward which they had been working feverishly for a full twelve months. To plant a colony across the gulf of space—a successful colony—later to be used as a steppingstone to other worlds....

"When you are dealing with frightened men, you're talking to ears closed to anything but what they want to hear."

“The Apaches have volunteered, and they've been passed by the psychologists and the testers. But they're Americans of today, not tribal nomads of two or three hundred years ago. If you break down some barriers, you might just end up breaking them all."

It all came back to the old basic tenet of the service: the end justified the means. They must use every method and man under their control to make sure that Topaz would remain a western possession, even though that strange planet now swung far beyond the sky which covered both the western and eastern alliances on Terra.

More than a generation earlier mankind had chosen barren desert—the "white sands" of New Mexico—as a testing ground for atomic experiments. Humankind could be barred, warded out of the radiation limits; the natural desert dwellers, four-footed and winged, could not be so controlled.

He was in countless Indian legends as the Shaper or the Trickster, sometimes friend, sometimes enemy. Godling for some tribes, father of all evil for others. In the wealth of tales the coyote, above all other animals, had a firm place.

"To make us more like our ancestors perhaps. It is part of what they told us at the project. To venture into these new worlds requires a different type of man than lives on Terra today. Traits we have forgotten are needed to face the dangers of wild places."

Basically, back on Terra, they had all been among the most progressive of their people—progressive, that is, in the white man's sense of the word.

The planet was on the tapes we brought back from that other world, and so it was known to the others who once rode between star and star as we rode between ranch and town. If they had this world set on a journey tape, it was for a reason; that reason may still be in force."

Kaydessa laughed. "Ah, they are so great, those men of the machines. But they are smaller and weaker when their machines cannot obey them."

The Apache had never been a hot-headed, ride-for-glory fighter like the Cheyenne, the Sioux, and the Comanche of the open plains. He estimated the odds against him, used ambush, trick, and every feature of the countryside as weapon and defense. Fifteen Apache fighting men under Chief Geronimo had kept five thousand American and Mexican troops in the field for a year and had come off victorious for the moment.

Travis settled his back against the spire of rock and raised his right hand into the path of the sun, cradling in his palm a disk of glistening metal. Flash ... flash ... he made the signal pattern just as his ancestors a hundred years earlier and far across space had used trade mirrors to relay war alerts among the Chiricahua and White Mountain ranges.

Men who had been dropped into their racial and ancestral pasts until the present time was less real than the dreams conditioning them had a difficult job evaluating any situation.

At dawn—the old time of attack. An Apache does not attack at night. Travis was not sure that any of them could break that old taboo and creep down upon the camp before the coming of new light.

"Knowledge—weapons, maybe. Can we stand against these machines of the Reds? Yet many of the devices they now use are taken from the star ships they have looted through time. To every weapon there is a defense."

"Take care, younger brother! This is not a lucky business. And remember, if one goes too far down a wrong trail, there is sometimes no returning—"

With a return of that queasy feeling he had known in the tower, Travis knew Manulito was speaking sense. They might have to open Pandora's box before the end of this campaign.

As Buck had pointed out, one's own ideals could well supply reasons for violence. In the past Terra had been racked by wars of religion, one fanatically held opinion opposed to another. There was no righteousness in such struggles, only fatal ends. The Reds had no right to this new knowledge—but neither did they. It must be locked against the meddling of fools and zealots.

The Time Traders by Andre Norton

Ideally, I should have read this book before reading its sequel, Galactic Derelict. As a result, I missed out on some of the suspense and mystery contained in the plot of The Time Traders. However, reading the second book first did not seriously affect my enjoyment of this first book in Norton’s series of novels featuring Ross Murdock.

Like Galactic Derelict, The Time Traders is primarily an action novel rather than one of introspection or big ideas. In spite of this, it does contain a fair number of interesting points about history and prehistory, even though more accurate and detailed information is now available concerning some aspects. For example, the end of the last ice age is now considered to be closer to our modern age than was thought in the 1950s. The author did produce a revised version of The Time Traders in 2000 to address certain issues and adjust the setting of the story from the 1970s to the twenty-first century. Another such revision concerns the overly pessimistic view of the prospects for space travel adopted in the 1958 edition, although there it does serve to explain why scientists turn their attention to the possibility of time travel instead.

Comparing this book and its sequel, I feel that The Time Traders is more tightly plotted and gripping than Galactic Derelict. In the latter book, there are some descriptions of periods when the crew is shut up in the spacecraft between planets which I felt became a little tedious. The first novel in the series does not suffer from any such monotony, and moves along quickly and fluidly all the way to its finale (although some readers may find the repetitious capture-escape-capture device slightly annoying. This did not bother me, though, since each experience was sufficiently different to maintain my interest). Of course, in common with much pulp fiction (such as the adventures written by Edgar Rice Burroughs), coincidence and almost unbelievable good and bad fortune create much of the tension and excitement.

Poul Anderson began to publish his Time Patrol series in the mid fifties, and there are some similarities between The Time Traders and those stories. Anderson’s work, however, was much more concerned with the nature of timelines and what would happen if they were changed. The style of writing in Time Patrol also became progressively more lyrical and the content increasingly profound and poignant (see The Sorrow of Odin the Goth for an excellent example).

I must say that I rate The Time Traders more highly than Galactic Derelict, despite the inventiveness apparent in the latter novel. I do recommend reading these two books in the order in which they were published to get the most out of them.

I suppose the logical next step for me would be to begin reading the third book in the series, The Defiant Agents.

Following are some quotations from the text of the book, selected to demonstrate the quality and style of the writing and some of the interesting content:

"The Reds shot up Sputnik and then Muttnik… . When—? Twenty-five years ago. We got up our answers a little later. There were a couple of spectacular crashes on the moon, then that space station that didn't stay in orbit, after that—stalemate. In the past quarter century we've had no voyages into space, nothing that was prophesied. Too many bugs, too many costly failures.

For some reason, though the Reds now have their super, super gadgets, they are not yet ready to use them. Sometimes the things work, and sometimes they fail. Everything points to the fact that the Reds are now experimenting with discoveries which are not basically their own——"

"Time travel has been written up in fiction; it has been discussed otherwise as an impossibility. Then we discover that the Reds have it working——"

"There is evidence that the poles of our world have changed and that this northern region was once close to being tropical. Any catastrophe violent enough to bring about a switch in the poles of this planet might well have wiped out all traces of a civilization, no matter how superior. We have good reason to believe that such a people must have existed, but we must find them."

Teach a man to kill, as in war, and then you have to recondition him later. "But during these same wars we also develop another type. He is the born commando, the secret agent, the expendable man who lives on action. There are not many of this kind, and they are potent weapons. In peacetime that particular collection of emotions, nerve, and skills becomes a menace to the very society he has fought to preserve during a war. He is pressured by the peaceful environment into becoming a criminal or a misfit.

"The men we send out from here to explore the past are not only given the best training we can possibly supply for them, but they are all of the type once heralded as the frontiersman. History is sentimental about that type—when he is safely dead—but the present finds him difficult to live with. Our time agents are misfits in the modern world because their inherited abilities are born out of season now.

"Do you know, Murdock, that bronze can be tougher than steel? If it wasn't that iron is so much more plentiful and easier to work, we might never have come out of the Bronze Age? Iron is cheaper and easier found, and when the first smith learned to work it, an end came to one way of life, a beginning to another.

The Beaker people were an excellent choice for infiltration. They were not a closely knit clan, suspicious of strangers and alert to any deviation from the norm, as more race-conscious tribes might be. For they lived by trade, leaving to Ross's own time the mark of their far-flung "empire" in the beakers found in graves scattered in clusters of a handful or so from the Rhineland to Spain, and from the Balkans to Britain.

"The Reds have made new discoveries which we have to match, or we will go under. But back in time we have to be careful, both of us, or perhaps destroy the world we do live in."

"When you have only one road, you take it," Ashe replied.

It was something that had so long been laughed to scorn. When men had failed to break into space after the initial excitement of the satellite launchings, space flight had become a matter for jeers.

…a gentleman named Charles Fort, who took a lot of pleasure in pricking what he considered to be vastly over-inflated scientific pomposity. He gathered together four book loads of reported incidents of unexplainable happenings which he dared the scientists of his day to explain. And one of his bright suggestions was that such phenomena as the vast artificial earthworks found in Ohio and Indiana were originally thrown up by space castaways to serve as S O S signals.

Do you have any idea how long ago that was, counting from our own time? There were at least three glacial periods—and we don't know in which one the Reds went visiting. That age began about a million years before we were born, and the last of the ice ebbed out of New York State some thirty-eight thousand years ago…

Civilizations rise, exist, and fall, each taking with it into the limbo of forgotten things some of the discoveries which made it great. How did the Indian civilizations of the New World learn to harden gold into a usable point for a cutting weapon? What was the secret of building possessed by the ancient Egyptians? Today you will find plenty of men to argue these problems and half a hundred others.

The Romans knew China. Then came an end to each of these empires, and those trade routes were forgotten. To our European ancestors of the Middle Ages, China was almost a legend, and the fact that the Egyptians had successfully sailed around the Cape of Good Hope was unknown.

"I might make one guess—the Reds have been making an all-out effort for the past hundred years to open up Siberia. In some sections of that huge country there have been great climatic changes almost overnight in the far past. Mammoths have been discovered frozen in the ice with half-digested tropical plants in their stomach. It's as if the beasts were given some deep-freeze treatment instantaneously."

We don't know too much about the ax people, save that they moved west from the interior plains. Eventually they crossed to Britain; perhaps they were the ancestors of the Celts who loved horses too. But in their time they were a tidal wave."

It is always impossible—he was conscious again with that strange clarity of mind—for a man to face his own death honestly. A man always continues to believe to the last moment of his life that something will intervene to save him.

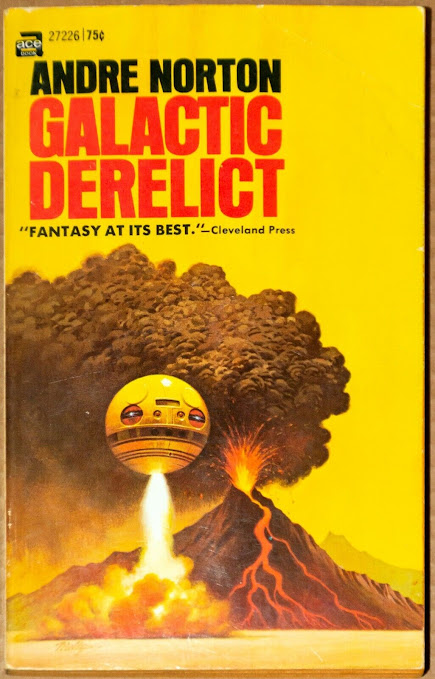

Galactic Derelict by Andre Norton

Published in 1959, Galactic Derelict is the sequel to The Time Traders, which came out the year before. The main character of the first book takes a back seat to a newcomer, Travis, who is Apache by descent, and proud of his traditions.