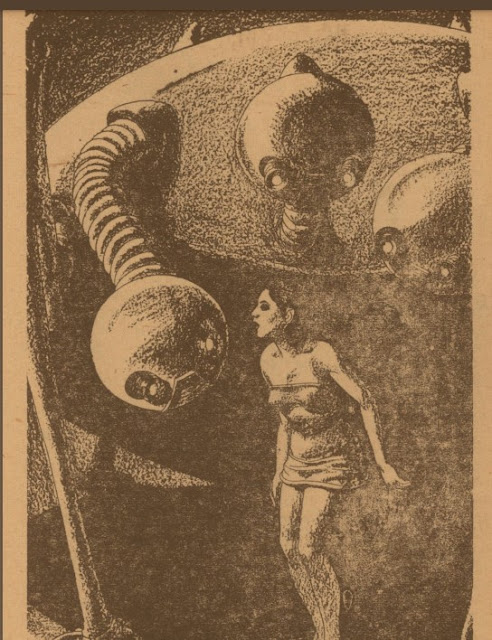

This story about how the Chinesian government colonized Venus first appeared in Galaxy Magazine in April 1959. The events related occur not long after Scanners Live in Vain, just as human lifespans are being lengthened from around a century and a half to four hundred years (through the use of the santaclara drug, stroon). Three hundred years later, an aged Dobyns Bennett is trying to recount his eyewitness experience of the Chinesian invasion of Venus to a rather reluctant reporter. The reader should remember that this story was written more than 60 years ago, and before the Venera landers and probes had shown the extremes of temperature and atmospheric pressure which exist on our sister planet. Nevertheless, When the People Fell shows humans needing suits and breathing apparatus to walk out on the surface of this world.

When Dobyns Bennett was a young man, he was at Experimental Area A, a base established on Venus by the Instrumentality. Dobyns was with Senior Scanner Vomact and his daughter Terza Vomact. The Senior Scanner Vomact in Scanners Live in Vain was made Chief for Space after Scanners become obsolete, and the Senior Scanner in When the People Fell describes himself as being already aged (probably around one hundred years old) and too old to benefit from the santaclara drug. I am not entirely sure whether they are one and the same person, although I rather think not. There seems to be a gap of a few centuries implied as existing between the two stories, so possibly by that time “Senior Scanner” had simply become a courtesy title. Indeed, the Vomacts are described as “a great family of scanners”. Terza is obviously the latest descendant of the Vom Acht Sisters who appear in the stories Mark Elf and The Queen of the Afternoon which are set some three millennia before her time.

The original Chinesian Jwindz government which had ruled all True Men had been brought down by the Vom Acht Sisters and their allies, but the Chinesian culture lived on for another three thousand years and by AD7000 there were seventeen billion people living on earth under the Goonhogo, the supreme leader of which was the Waywonjong.

This is still the Second Age of Space, and The Instrumentality apparently wishes to colonize Venus, but is stymied by native creatures known as Loudies. They float around just above the surface of the planet and reproduce at a prodigious rate. They are harmless under normal circumstances, but destroying even one of them results in dire consequences. The Experimental Area has not found a workable solution to the problem.

The situation changes abruptly and unexpectedly when the Waywonjong orders a massive invasion and colonization of Venus. The representatives of the Instrumentality cannot see how colonization can be achieved due to the large numbers of Loudies, but the Goonhogo employs a crude but extremely effective solution to this difficulty, despite the fact that this method takes a heavy toll in human lives.

When the People Fell is perhaps the Cordwainer Smith story with most overt references to China, Chinese history, and the plight of the common people through the ages, especially in the first half of the twentieth century. The terms used in the narrative are obviously Anglicized renderings of certain Chinese words, and they are explained by Dobyns Bennett for the benefit of the journalist who does not understand them. Here is a list of those terms:

Loudies = 老者 Ancient Ones

Nondies = 男子 men

Needies = 女子 women

Showhices = 小孩子 children

Goonhogo = 共和國 republic

Waywonjong = ???? Supreme Ruler of the Goonhogo

(Waywonjong in the book The Rediscovery of Man is spelled Waywanjong in the original Galaxy Magazine version of the story).

(I really cannot think of how Waywonjong should be rendered in Chinese, but I am pretty sure that the author had something specific in mind. Characters like 威 wei、萬 wan、將 jiang /總 zong most naturally spring to mind, but they do not fit together in a meaningful way. If anyone has any other ideas, please do let me know).

Modern readers may take the descriptions in this story as derogatory or even racist references to the Chinese people. However, after learning how familiar the author was with China and its culture and history, and about the years he invested in the country and its welfare, it is difficult to maintain such a viewpoint. More likely, Paul Linebarger as Cordwainer Smith is showing us how the Chinese people, although frequently ravaged by war, famine and poverty, through their sheer numbers and tenacity overcome problems deemed unsolvable by others. “It was crazy and impossible, but they won!” Says the aged Bennett.

The key to this interpretation is provided by a short but memorable scene which occurs near to the end of the story. A nondie is building some sort of shelter with his bare hands. When he is asked what it is for, Vomact is astonished at the reply. But pondering on that response enlightens us as to what the Chinese people may have needed most at the time when the author penned this tale.

The narrative structure of When the People Fell is similar to The Lady Who Sailed the Soul in that it is a recollection of former times by someone in a future era. Other comparable points are how the impression the title gives changes before and after you read the story, and the fact that it ends on a poignantly romantic note. Having said that, I must also add that of the stories by Cordwainer Smith I have read so far, this one contains the most graphically disturbing imagery.

Overall, When the People Fell is a fascinating tale which increases our knowledge of the relatively early history of the Instrumentality, and how and when the last of the separate earthly governments began its decline into oblivion.

The Lady Who Sailed the Soul

This short story was first published in Galaxy Magazine in 1960.

It opens with a scene which is occurring at some unspecified time in the future when the "planoforming" form of space travel has already been discovered. A little girl playing with a toy animal asks her mother about "sailors", and her mother proceeds to explain how people used to sail out to the stars and their planets in spacecraft powered by gargantuan sails. The history has already acquired a legendary aura of romance in the mother's mind.

The story then switches to the past (to somewhere between AD6000 and AD7000 according to the Concordance to Cordwainer Smith), and probably the days after the Scanners, since they are not mentioned at all. We begin to read about experiences in the life of Helen America. Helen resents her narcissistic and capricious mother, and is determined to display none of her traits. Various other factors make Helen appear aloof and cold outwardly, although we find out that her true nature is very different.

The main part of the narrative is essentially how and why Helen becomes the first female interstellar sailor ever, and why sailors are providing a valuable and heroic service to mankind in this period.

Quite a lot of effort is invested into explaining the technical details of how a sailor is prepared for a journey and how a special drug enables an "objective " period of decades to pass in mere weeks from the point of view of the pilot. Even the ratio between the objective and the subjective passage of time is clearly stated. I think that the drug which is used may possibly be related to the method which Adam Stone developed and which rendered the Scanners obsolete (See Scanners live in Vain by Cordwainer Smith).

The narrative clearly states that the sails are able to propel the craft at "something not far from the speed of light itself". I am pretty sure that Cordwainer Smith and his wife Genevieve (who collaborated on this story) would have been aware of the effects of Einsteinian Special Relativity on any objects or persons traveling at velocities approaching the speed of light. These effects would seem to result in outcomes which are the very opposite of those described in the narrative, and would make the use of any drug such as the one described unnecessary. Of course, reaching such a velocity may have been a rare phenomenon, as it is only mentioned once during Helen's voyage.

The portrayal of travel over interstellar distances, although superficially detailed and technical, is certainly not the stuff of hard science fiction. And we should not expect it to be, since the story itself has apparently already become part of the mythology of a past which is imperfectly and incompletely remembered. We have no way of knowing how much of the story is provided for the benefit of the reader, and how much was part of the legend about the days of sailing which was preserved by future generations.

Chinese legends and unofficial histories, as I have noted in another review, do not have a problem with illogical elements or internal contradictions, and many commentators agree that the short stories of Cordwainer Smith taken as a whole have underlying structures similar to those of Eastern mythological tales.

Both Helen and the other main character (Mr. Gray-no-more) show themselves ready and willing to make great sacrifices for each other, so much so in fact that they are compared to the tragic Medieval lovers Heloise and Abelard. You could read ideals of traditional Chinese virtue into their decisions in that they are examples of choosing what is difficult for yourself in order to make life easier for another person.

君子自難而易彼,眾人自易而難彼。

The person of noble character takes on the hard tasks and lets others do the easy things; most people, on the contrary, choose the easy things and let others deal with the difficult tasks.

(Excerpt from Mozi Book 1)

Near to the end, the scene reverts to the mother and daughter we met at the beginning. I found this part particularly poignant. There is a grating juxtaposition of sentimentality and an almost mocking cold-heartedness. And like the rest of this tale, there is a preoccupation with the passage of time and its all-too-often undesirable effects. (One point I found illogical was when the daughter, now grown up, says that "the world ought to get rid of sailors". If planoforming had superseded craft with solar sails and was already the norm, there should by then have been no sailors to get rid of.)

The inevitable, unavoidable and often cruel effects of the passing of time are often referred to in ancient Chinese texts and poems.

子在川上,曰:「逝者如斯夫!不舍晝夜。」

On the river bank, Confucius sighed and said, "Time passes just like this river water! It flows unceasingly day and night."

(Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius)

「金烏玉兔最無情,驅馳不暫停。」

The Sun and the Moon are most pitiless, forever driving relentlessly onward. (Time and tide wait for no man)

(From a Song Dynasty Poem by Zhang Lun) 宋詩 張掄《阮郎歸》

The title of this piece likely also has more than one meaning. Before you read it, "sailing the soul" probably hints at certain spiritual connotations (souls have been compared to sails which need to be filled with the spirit of inspiration, love or some other intangible force for our lives to move forward and have meaning), although you quite quickly find out that it is used in a much more prosaic way in this story. Nevertheless, the spiritual sense of the first impression lingers. We may also ponder why the story was not entitled "The Girl (or Woman) Who Sailed the Soul." I think that perhaps the word "Lady" also deepens the mythological aspect of this tale which is already partly shrouded by the shifting mists of time. Indeed, the narrative itself states that apart from the long-dead protagonists themselves, no one really knew what happened, especially concerning the events surrounding the relationship between Helen and Mr. Gray-no-more.

The story published in Galaxy in 1960 is divided into ten short chapters, but the later version has twelve, including an extra part at the end which movingly concludes the story of Helen and Mr. Gray-no-more. This ending is apparently included for the benefit of the reader and is one of the elements which was only known to the two main characters, and so probably did not become part of the legend. According to historical information on one website (I cannot vouch for its accuracy), there really was a "Helen America" who lived in the nineteenth century. Although her character does not seem to have been at all like the Helen of our story, she evidently felt a similar need at times in her life to leave her background behind her and start afresh.

(Website address: http://www.fourth-millennium.net/cordwainer-vr/lady-who-sailed-the-soul.html).

Scanners Live in Vain

Scanners Live in Vain is a short story published by Cordwainer Smith in 1950, and it is considered a seminal work of science fiction. It was finished in 1945, but did not find a publisher until five years later, partly because its content was considered “too extreme”.

It was fortuitous that the story came to be noticed at all, since it was published in a science fiction magazine with a very low circulation (Fantasy Book). However, that publication happened to carry a piece of work by the more well-known author Frederik Pohl, who read Smith's story and recommended it to others. After a hiatus of about five years, Smith began to write other stories set in the same universe (The Game of Rat and Dragon in 1955, and Mark Elf in 1957), including some which provide the backstory to this one.

The narrative begins abruptly by throwing a series of unexplained terms at the reader, stimulating curiosity about what could be going on, although quite a lot can be deduced from the context.

The story is set in a distant future in which space travel has become commonplace (circa AD6000 according to the Concordance to Cordwainer Smith). The protagonist at one point states that he was (born in?) the 182nd Year of Space, which presumably refers to the Second Age of Space if we take the whole Instrumentality chronology into account.

Nevertheless, space travel is fatal to humans if they do not hibernate for the duration of long flights due to something called the "Great Pain". A special group of people is therefore created through a process of physical modification, and these individuals are able to stand the pain of traveling in a conscious state through deep space. The cost of this modification, however, is the loss of all human senses (apart from sight), and instruments attached to the body must be continuously monitored by their users to "scan" both basic physical functions and everything in the environment around them instead of feeling these things naturally. Most of these modified humans are criminals (habermans) who have been forcibly drafted into service, but the Scanners who oversee them on space flights have made the sacrifice voluntarily (habermans by choice) and are therefore held in the highest esteem within society. Only through a special process called "cranching" can Scanners temporarily experience their human senses and emotions again, and this cannot be done too often or for too long without adverse effects.

Next to the members of the Instrumentality, the Scanners enjoy the highest position in society, and would only feel threatened if a discovery were to come to light that might render their role obsolete. They do not consider such a scenario very likely, but if it were to occur would they all agree on what should be done about it?

The Concordance suggests a reason why the author may have chosen the word “haberman”, but the explanation seems to conflate at least two different explanations of the origin of the German term “Haberfeldtreiben”. According to the German version of Wikipedia, the Haberfeldtreiben were informal “tribunals” organized by the local members of agricultural communities in Bavaria to shame persons were deemed to have acted wrongly but whose behavior was not punishable by law. The people involved would disguise themselves so as not to be recognized and surround the home of the “wrongdoer”. They would then proclaim that they were meting out punishment in the name of Emperor Charlemagne, and proceed very loudly to read out poetry and sing songs which mocked the victim and generally to make a racket (often in the night) which drew the attention of all local residents to the “crime” of the person accused. Haberfeld itself means “oat field”, and some commentators believe that “fallen maidens” were forced to run through the crops while being mocked and possibly whiplashed. The heyday of the practice seems to have been during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and it was formally banned in 1922. The same article points out that one scholar has counted twenty different possible explanations for the origins of the term Haberfeldtreiben, and now it is not possible to say which one is most accurate. A key point which the Concordance brings out which seems to prove that Cordwainer Smith at least had this practice in mind is the fact that the grandfather of Charlemagne was Charles Martel, and Martel is the name of the protagonist in this story. Of course, there is a logical problem in that the habermen of the Haberfeldtreiben were the persecutors, whereas the habermans in Scanners Live in Vain are the criminals, described in the story as “the scum of Mankind. Habermans are the weak, the cruel, the credulous, and the unfit. Habermans are the sentenced-to-more-than-death.” But this should not worry us too much, since the author probably took the name from an assortment of ideas in his head and was not seeking to be strictly logical in this etymological detail. The Martel link seems to me a pretty conclusive indication that Smith was thinking about the abovementioned tradition. The Concordance also states that “A possible alternative or additional meaning is from halb (German) = half: halfman?”

Vomact the Senior Scanner naturally reminds us of the Vom Acht family mentioned in Mark Elf (1957) and The Queen of the Afternoon (1978). In the latter story, Carlotta Vom Acht is already known by the title of The Vomact, and her sister Juli succeeds her in his position. Scanners Live in Vain states that Senior Scanner Vomact “was said to be a descendant of some Ancient Lady who had traversed, in an illegitimate and inexplicable fashion, some hundreds of years of time in a single night. Her name, the Lady Vomact, had passed into legend; but her blood and her archaic lust for mastery lived on in the mute masterful body of her descendant.” The Lady Vomact in question is generally supposed to be Juli Vom Acht of The Queen of the Afternoon.

Chang is one of the Scanner colleagues of Martel. The narrative relates: “It’s strange, thought Martel, that more Chinese don’t become Scanners. Or not so strange, perhaps, if you think that they never fill their quota of habermans. Chinese love good living too much. The ones who do scan are all good ones.” It thus seems that certain Chinese cultural traits have survived into AD6000. One obvious reason why Chinese men may not be eager to become Scanners relates to the importance of producing heirs and continuing the family line in Chinese society. Martel is unusual among Scanners in that he is married, and Vomact describes Martel’s marriage as a “brave experiment”. Even so, with only a few days in a “cranched” state each year, he would likely have difficulty producing children. Furthermore, the traditional Chinese culture seems to foster a practical turn of mind which may promote “good living”. Of course, by AD6000 Chinese people may have acquired more of a taste for luxury, but at present they are known the whole world over for being industrious and realistic. This is not to say that Chinese people do not ever act for purely altruistic reasons, but it does mean that they tend to avoid extremes which are unlikely to bring commensurate benefits. As a person who has been living in Taiwan for decades, I observe that certain behaviors which are major problems in the UK hardly exist here at all. Among these is the wanton vandalism of public facilities. The people I have asked about this in Taiwan seem rather nonplussed at the question being asked at all. They reply that why would someone want to waste their time and energy wrecking something for no reason. First of all, there is the risk of getting caught and being punished by the authorities, and secondly the offender gains no benefits from the act even if he or she is not apprehended. This is a very logical and practical way of thinking. Thus, Martel discerns that although not many Chinese people become Scanners, those who do are good ones.

I think that the meaning of the title “Scanners Live in Vain” may have more than one connotation. Most Scanners believe that only by becoming obsolete would their sacrifice and lives have been in vain. This is the more overt meaning which is very obvious in the story. But at the same time, much of the narrative, including the finale, revolves around Martel’s desire for normality and a closer relationship with his wife. It is therefore evident that Martel feels that Scanners live in vain because they miss out on the kinds of human experiences which create a sense of meaning in the existence of most people.

This short work showcases Cordwainer Smith's vision in several areas, for example in his idea of how a futuristic government and society may operate, the influence new technology may have upon human psychology, and the advantages and disadvantages of physical modification. Of course, a major factor which makes it relevant to the reader is that it, like many other notable works of science fiction, probes the central and fundamental question of what it means to be human.

The Queen of the Afternoon

Internal details reveal that this short story is set two hundred years after Mark Elf (circa 4200AD), and that the events probably take place in the same location. The Earth is well on the road to recovery after the atomic wars of past ages.

We meet the second Vom Acht sister, Juli, who is deliberately brought down from suspended animation in orbit around the Earth for a very specific purpose. The title of the story may be a reference to her time of arrival.

Whereas in Mark Elf, people were divided into Morons and True Men, along with the appearance of a person derived from a bear, in this sequel there are further classifications. The Morons seem to have vanished, while there is the addition of Unauthorized Men, the Unforgiven, Underpersons, and imperfect or failed experimental forms of Underpersons or modified animals, one of whom becomes an important character in the story. Mark Elf left the reader with the impression that True Men were at the top of the hierarchy, but The Queen of the Afternoon disabuses us of this notion, explaining that the Chinesian Jwindz are the ultimate controllers.

Interesting points include the first overt mention of the Instrumentality, along with a description of its original function. A small number of Manshonyaggers are still operative after two centuries, but are no longer much of a danger, partly due to the fact that the Unauthorized Men can sense them telepathically while they are still approaching, and because others have learned True Doych (German) due to the presence of Carlotta. They are thus able to command the machines to leave them alone.

Although there are differing opinions about the author’s choice of the word Jwindz for the aloof and unapproachable rulers of the world (one idea is that it is related to the Djinn of Middle Eastern folklore), I think the most obvious and reasonable explanation is that the name is derived from the Chinese “君子” (Junzi in Pinyin), a designation which appears frequently in early Chinese philosophical texts such as the Analects of Confucius and The Hundred Schools of Thought. Indeed, the Chinese version of The Rediscovery of Man uses “君子” (Junzi) in its carefully-considered translation.

In ancient China, Junzi always referred to males, and the associated behavior and deportment was the standard to which educated men aspired, especially those who wished to lead their fellows in some capacity. In an effort to make the eminently practical wisdom found in the ancient texts more accessible and applicable to modern readers, my own translations of Junzi are as follows:

person of integrity; person of noble character; person of principle; person of lofty ideals

More information can be found on my blog at: https://hoppy500.blogspot.com/2021/09/practical-points-from-four-chinese.html

The nature of the Jwindz seems to be a corruption of the Confucian ideal regarding what constituted a Junzi. Ironically, people who refer to themselves as Junzi, or who allow others to address them by such a title, would by doing so prove that they are not Junzi at all, since those who are truly noble of character should be modest and self-effacing. The standard of the Junzi is an ideal to be strived for continuously, but not one which can ever be perfectly achieved. The manner in which the Jwindz treat the True Men (which includes allowing True Men to imagine that their rulers are perfect), and their detachment from all other intelligent beings on Earth thus indicate a conceit and lofty arrogance which constitutes a transgression against the Confucian ethics by which rulers should conduct themselves.

The Queen of the Afternoon was not published until 1978, some twelve years after the death of Cordwainer Smith (Paul Linebarger). It first appeared in Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine (Vol. 39 No. 4) in that year. The Concordance to Cordwainer Smith merely states than the story was “by Genevieve Linebarger based upon an unfinished story, published posthumously”. Published posthumously must refer to the death of Paul Linebarger, since Genevieve did not pass away until 1981. I wonder how much of this story had already been written by her husband, and to what extent his widow added to it. If anyone knows more about this, I would certainly be interested to know.

There is a pathos in The Queen of the Afternoon which is expressed in the following poem which Juli reads from an ancient inscription, and through the events which subsequently take place.

Youth

Fading, fading, going

Flowing

Like life blood from our veins…

Little remains.

The glorious face

Erased,

Replaced

By one which mirrors tears,

The years

Gone by.

Oh, Youth,

Linger yet a while!

Smile

Still upon us

The wretched few

Who worship

You…

The Queen of the Afternoon is longer and has more of a storyline than the preceding Mark Elf. Every paragraph is packed with details which begin to unfold more substantially the history of the Instrumentality of Mankind. It is therefore an indispensable part of the Instrumentality saga.

Mark Elf

This story, which was first published in Saturn Magazine in May 1957, draws the reader in right away with the description of an ancient spacecraft being brought back to the Earth. 16000 years is said to have passed since it was launched at the end of World War II. The occupant of the rocket has been in suspended animation and is revived upon landing, but finds the environment very much changed. There is a basic division of society into Morons and True Men.

The story progresses in a linear fashion which ties each part together, but it reads more like a series of vivid impressions than a simple narrative. It feels somewhat like the beginning of a longer novel.

Although Scanners Live in Vain was published earlier in 1950 (written in 1945 but took five years to find a publisher) and succeeds it in Instrumentality chronology, Mark Elf provides more information about the “Manshonjaggers” referred to therein. We find out something about their origin and the meaning of the name.

Another interesting point is that we meet an underperson (or an early form of one) for the first time.

The reference to 16000 years having passed while the rocket was in orbit presents a bit of a problem for the chronology of the Instrumentality as a whole, as this would place the events of Mark Elf after those described in stories like The Ballad of Lost C’Mell and Norstrilia, whereas it is pretty clear that they occur well before those accounts. The Concordance to Cordwainer Smith uses the chronology of J.J. Pierce for Mark Elf, placing the events described in it around AD4000, probably on the basis that in this way it fits the overall timeline. Unlike some other writers, like Tolkien, Cordwainer Smith does not seem to have been overly concerned with internal consistency, probably because he intended everything to have a mythological and symbolic feel to it anyway.

Western thought greatly emphasizes logical consistency (this can even be seen in religions like Christianity), whereas Chinese thought is quite different. Like the ancient Egyptians, the origins of many of their gods and historical tales are mythological or even purely fictitious, and there can be several contradictory accounts of the same important event. This appears to cause no sense of cognitive dissonance for believers, as it certainly would for people who have been educated according to Western tradition. It may be partly for this reason that Cordwainer Smith did not attempt to go back and smooth out or correct the inconsistencies which exist between some of his stories. This could actually be viewed as one of their “Eastern” traits.

No, No, Not Rogov!

This is a highly engaging short story by Cordwainer Smith. Although the Instrumentality of Mankind is not mentioned, we do nevertheless get a glimpse of the distant future.

The story begins in the Soviet Union in the days of Stalin. Nikolai Rogov and his wife Cherpas are both brilliant scientists utterly dedicated to the Soviet cause. They are assigned to the top-secret Project Telescope and sent to an isolated location. Their work is closely monitored by two members of the secret police. Rogov and Cherpas hope to develop a machine which can read and influence human minds over vast distances, since this would give the Soviet Union an unsurpassable advantage in its fight against the Western capitalist countries. On the very cusp of success, events occur which bring entirely unexpected outcomes.

The story quickly captures the imagination of the reader and very effectively maintains tension from start to finish. Firstly, we want to find out if the machine will work, and if so, what the operators will see. Secondly, although the characters try to remain as cold and dispassionate as possible (as selfless communists), there is great psychological tension between the various individuals.

No, No, Not Rogov! is an obvious indictment of the Soviet political system which existed in the era in which this work was written, and it shows that however devoted someone may be to an ideology, they will inevitably come into conflict with it in some ways on a personal level.

From the introduction, narrative content, and conclusion, it is not difficult to understand why this author is regarded by many as a master of the short-story format.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not seem to be working. Many people say they have left comments, but I do not receive them. I have not been able to overcome the problem, unfortunately.